(The latest Rockhill Neighborhood Association newsletter contained two articles with some interesting neighborhood history; they’ve given us permission to reprint them. Yesterday, Rockhill resident Todi Hughes profiled Laura Nelson Kirkwood. Today, UMKC Professor Emeritus Robert M. Farnsworth shares a story at the home of I.H. Kirkwood, later the Rockhill Tennis Club, which came to his attention while researching his biography of Leon Mercer Jordan.

Reprinted with permission from the Rockhill Neighborhood newsletter by Robert M. Farnsworth

In 1917 there was a brutal race riot in St. Louis that quickly captured the attention of the entire nation. On July 6th former President Theodore Roosevelt got into a ferocious argument with Samuel Gompers, the head of the American Federation of Labor, at Carnegie Hall in Philadelphia. The clash was widely reported in the national press, and particularly in the black press. The Carnegie meeting was called to greet a delegation from the new revolutionary Provisional Government of Russia, but that became a sideshow with the American press to the debate on race and labor sparked by Roosevelt and Gompers over their different takes on the riots in E. St. Louis.

Harper Barnes in Never Been a Time: the 1917 Race Riot that Sparked the Civil Rights Movement, focuses the disagreement: “‘Before we speak of justice for others,’ said Roosevelt, ‘it behooves us to do justice within our own household. Within a week there has been an appalling outbreak of savagery in a race riot at East St. Louis, a race riot for which, as far as we can see, there was no real provocation.’ Gompers reacted to Roosevelt’s remarks by insisting that there had been plenty of provocation. He blamed the violence on ‘reactionary’ employers who had imported black strikebreakers from the South. ‘The luring of these colored men to East St. Louis is on a par with the behavior of the brutal, reactionary and tyrannous forces that existed in Old Russia,’ he declared.”

The audience at Carnegie Hall was vocal in support of both sides, and the New York Times later noted, “It was not a mere quarrel between Roosevelt and Gompers, it was a division in the crowd—a crowd gathered together from all the friends of new Russia—Socialists and workmen who saw chiefly the economic provocation of the riot, and members of other classes who had more feeling of the horror.”

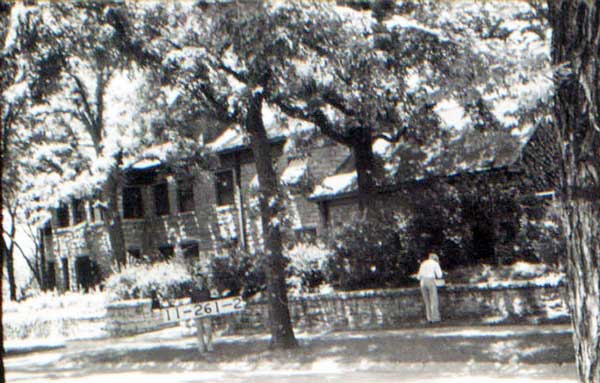

In September, Roosevelt spoke at a banquet in Kansas City attended by the business elite of the city. He was the guest of I. H. Kirkwood, William Rockhill Nelson’s son-in-law. A delegation of prominent black citizens was invited to visit him at Kirkwood’s palatial home, the site until recently of the Rockhill Tennis Club.

Nelson Crews, Leon H. Jordan’s [the father of Leon Mercer Jordan, the founder of Freedom, Inc.] political rival, but also good friend, was spokesman for the delegation, which included Dr. J. Edward Perry, Jordan’s friend from the days of the Spanish American war. [Dr. Perry founded Perry’s Sanitarium that later became Provident Wheatley Hospital]

Crews thanked Roosevelt for his “manly and courageous stand for the race in the recent controversy with Samuel Gompers. . . .when Abraham Lincoln uttered those splendid words in which he said, ‘Government of the people, for the people, and by the people shall not perish from the earth,’ he gave utterance to a lofty and magnificent sentiment, but when you, Colonel Roosevelt, gave utterance to that stirring sentiment, ‘All men up and no men down,’ you forever endeared yourself to every Negro beneath whatever flag he may live in the civilized world.”

Dr. William H. Thomas, pastor of Allen Chapel, then asked the former president for “a message of inspiration to carry to our people.” Roosevelt told of having requested permission to organize a brigade of colored troops that he would have led in the nation’s current war with all the other officers being colored officers. “I would have expected every man from that regiment to have measured up to the highest possible standing because I knew more would be expected of them than of other elements in my regiment, but as I was not permitted to organize that brigade, I can only say to you: ‘Be brave, be not weary in well doing, be patient, but progressive; trust in God and respect your fellows; always remembering that all things which are possible are not always expedient.”[1]

[1] Kansas City Sun, May 12, July 7, September 29, 1917; August 10 & 17, 1918; Harper Barnes, Never Been a Time, pp. 2, 143-144, & 178-179.