By Mary Jo Draper

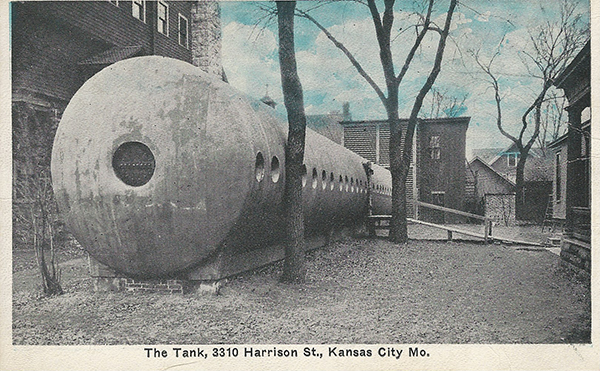

I recently stumbled upon a vintage postcard that showed a huge metal structure called “the tank” at 3310 Harrison. A little research turned up a fascinating story about the tank and the reaction of the neighbors in the North Hyde Park neighborhood when it was in place in the 1920s.

The Kansas City tank is part of what has been called one of the strangest experiments in medical history. “The tank” was an invention of Dr. Orval J. Cunningham, who was on the staff of the University of Kansas Hospital in the early 1900s and the operator of a sanitarium in the North Hyde Park neighborhood where the tank sat in the 1920s. Prodded by a desire to help save Kansas City patients from the flu epidemic in 1918, Cunningham put his inventive talents to work to test out a theory – that some diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and syphilis were caused by living organisms that fail to grow in the presence of oxygen.

Cunningham theorized that compressed air could restore health by restoring oxygen to the blood. His experimental hyperbaric tank caused a variety of reactions: a millionaire wanted to fund its wider application; Midtown Kansas City residents complained about its impact on their property values; and the American Medical Association denounced Cunningham for “advancing a thesis that is altogether without scientific proof.” After the experiment in Kansas City, Cunningham moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where he built an even larger steel structure.

As part of our Uncovering History Project, the Midtown KC Post is examining each block in Midtown. A set of 1940 tax assessment photos is available for many blocks.

Today, an in-depth look at 3310 Harrison. Next week, details about the history of the rest of the block from 33rd to 34th between Campbell and Harrison.

Who Was Orval Cunningham?

The scientist behind this experimental treatment facility, Dr. Orval Cunningham, first shows up in local history as the chief anesthetist of the University of Kansas School of Medicine in 1916. According to two researchers (Orval Cunningham: The Man, His Machine, His Tank in Kansas City and Cleveland, by Anthony L. Kovac, M.D. and George S. Bause, M.D., University of Kansas Medical Center), Cunningham had invented an early anesthesia machine, but when the 1918 flu epidemic hit, his attention shifted from anesthesia to creating a “therapeutic (hyperbaric) apparatus.” He based his theory on his observation that people with lung disease improved when they moved from Denver to Kansas City and wondered if that was because of lower atmospheric pressure.

“He designed and built a tank at the University of Kansas Hospital in 1918 and credited it for saving the lives of two people seriously ill with pneumonia. He then began testing the tank for treatment of hypertension, diabetes, and syphilis.”

Cunningham Moves His Research to Midtown

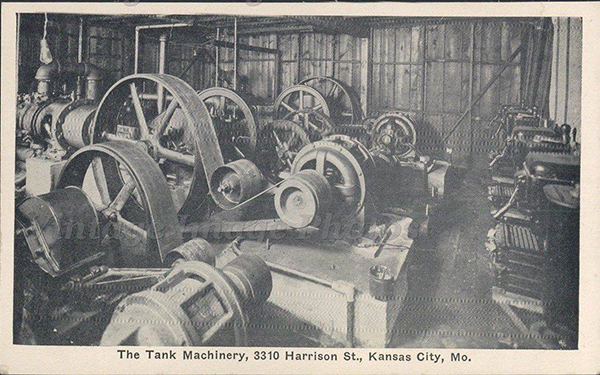

In 1920, Cunningham revealed the purpose of a giant steel tank (seen above) that had appeared in the sideyard of 3310 Harrison. He told the Kansas City Star that, based on the success of treatments at the University of Kansas, the tank would be used in treating disorders by introducing more oxygen into the lungs. The tank, 80 feet long and 10 feet in diameter, was divided into 36 compartments on each side of a long hall. The tank resembled a Pullman train car and was, in fact, outfitted with beds supplied by that company. The compartments had showers, dressing rooms, and closets so that patients could sleep in the tank.

The neighbors of the Cunningham Sanitarium reacted negatively to its operation in the quiet residential area. They complained for months about the noise and vibrations of the engines required to run the tank. They worried people with communicable diseases were being housed there. They asked a judge to bar patients from sitting in the yard “or walking on canes or crutches as their presence might have a depressing effect on others in the neighborhood.” The judge agreed.

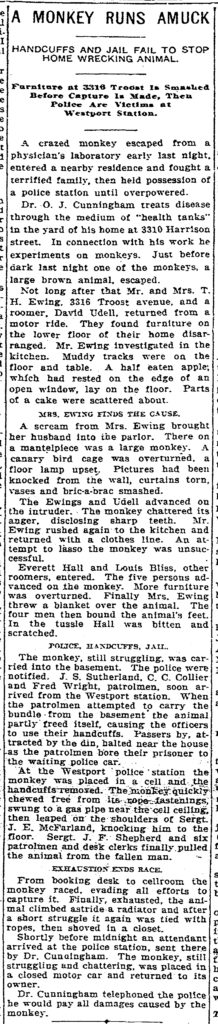

Another incident also raised public concern—the escape of one of Dr. Cunningham’s monkeys, which neighbors said terrorized the neighborhood.

Kansas City Star, April 20, 1924.

In the end, it wasn’t the neighbors’ complaints but a tantalizing offer from a wealthy financier that led Cunningham to abandon his tank in Kansas City and build an even bigger hyperbaric chamber in Cleveland.

Cunningham Moves to Cleveland, and An Even Bigger Tank

H.H. Timken, known as the “Baron of Bearings,” was the board chairman of the Timken Roller Bearing Company in Canton, Ohio. After a friend (or Timken himself, according to some accounts) underwent what he considered successful treatment in Kansas City, Timken made Dr. Cunningham an offer that eventually led to this national newspaper announcement.

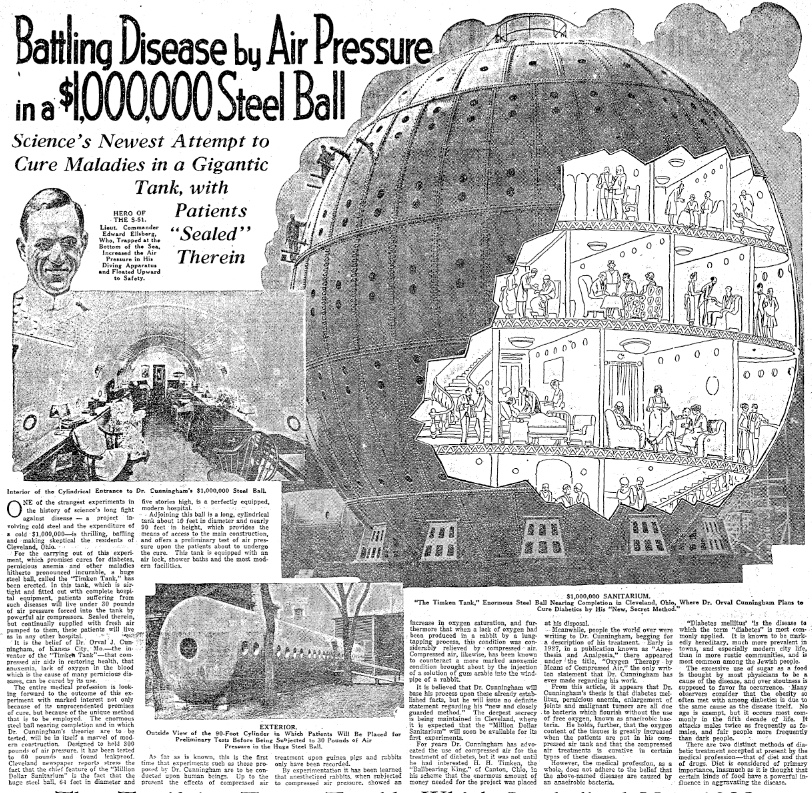

“One of the strangest experiments in the history of science’s long fight against disease – a project involving cold steel and the expenditure of a cold $1,000,000 – is thrilling, baffling and making skeptical the residents of Cleveland, Ohio.” Beaumont Journal, Sept. 28, 1928

Timken gave Cunningham a million dollars, and the doctor oversaw the construction of a five-story, 900-ton steel ball 64 feet high and 38 rooms. The ball had a first-floor dining room, a top-floor reception room, and three floors of bedrooms.

Courtesy Cleveland State University. Michael Schwartz Library. Special Collections.

The Cleveland Cunningham Sanitarium was located outside of residential areas, but criticism was already coming from a new direction was the facility was completed. The American Medical Association warned patients to be skeptical of Cunningham’s claims.

Dr. Cunningham claims unusual results in the treatment of such serious conditions as diabetes, syphilis, carcinoma and pernicious anemia, but has published no case reports or furnished the medical profession with any evidence to support the claims. To explain his alleged results, Dr. Cunningham advances a thesis that is altogether without scientific proof, namely, that diabetes mellitus, pernicous anemia and carcinoma are due to an anaerobic form of pathogenic bacteria. Under the circumstances, is it to be wondered at if the medical profession looks askance at the ‘tank treatment’ and intimates that it seems tinctured much more strongly with economics than with scientific medicine?” It is a mark of the scientist that he is ready to make available the evidence on which his claims are based. Dr. Cunningham has been given repeated opportunities to present such evidence.

Journal of the AMA, May 5, 1928, pp. 1494-96

Cunningham ran the sanitarium in Cleveland until 1934, when it was sold and closed in 1937. The site and the huge steel ball sat unused until 1942, when they were dismantled to be used as scrap metal during the war.

I have found no details on what happened to the Kansas City tank, but I would love to hear anything readers might know.

UPDATE: March 9, 2018

Our readers DID have more information about this fascinating story.

I grew up this block in the 80’s. Crazy story. Feel sorry for the monkey, and the Dr.’s theory about the oxygen cure-all sounds a bit off. Thank you for sharing these stories. So fun to read!

interesting! thanks for sharing all this great history!

Mary Jo, I did enjoy reading the stories about the tank, Dr. Cunningham, and about the monkey.

Thank you for writing the information.

Pingback: North Hyde Park block drew early prominent families | Midtown KC Post

Pingback: Hacia el hospital esférico – Tecnología Obsoleta

Mary Jo,

I recently found a letter that my gread grandmother Nora Phillips wrote to her family while she was staying in the “tank”. From her description of the tank and the fact that she wrote the letter on Orval J Cunningham’s stationary, I Googled and found your article.

Nora died in 1925 and there is no date on the letter. I can only assume she became ill after the flu pandemic and this was the latest in treatment for her condition. From your article, I’m guessing cancer. If you are interested in a copy of the letter, let me know and give me an address to send.

Thank you so much for writing this and posting.

Pingback: North Hyde Park block drew early prominent families at Midtown KC Post

I just ran across this article and I have old photos of this tank sitting beside the house. I never knew what it was until I read this article. My great grandfather was either an investor or a patient. I also have pictures of him with multiple people around the house and seating inside the tank. This article has solved a mystery for me.