Before the Walnuts, among Kansas City’s most high-end apartments, were erected in 1929, a large home stood on the same site at Fifty-first and Wornall. The mansion—also known as the Walnuts —became a famous venue for entertaining well-to-do city residents until a developer saw the site’s potential as a luxury residential hotel.

As part of our Uncovering History Project, the Midtown KC Post is examining each block in Midtown. A set of 1940 tax assessment photos is available for many blocks.

Today, block between 50th and 51st from Wyandotte to Wornall.

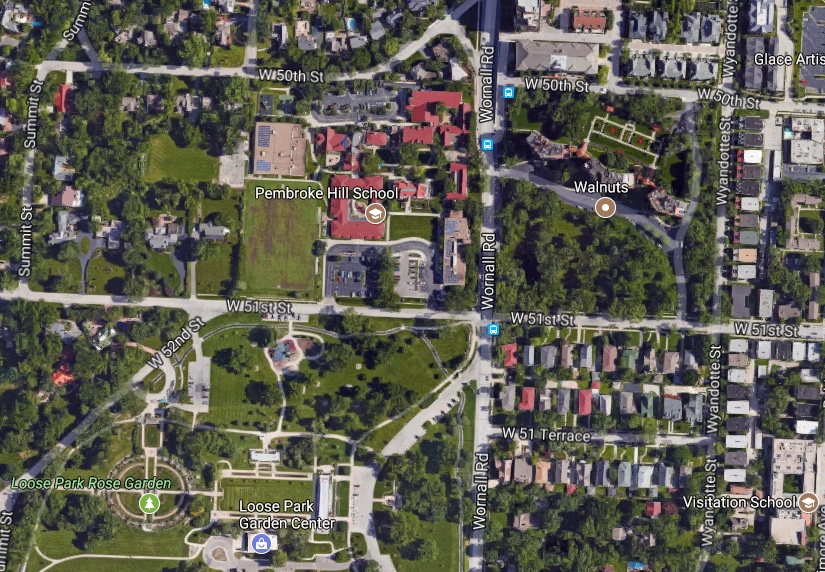

A recent Google aerial view of the Walnuts.

The Walnuts Mansion Took Name from Wooded Lot

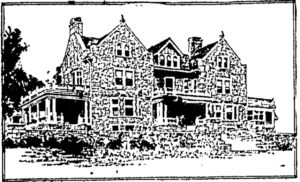

A 1917 sketch of the Walnuts before the mansion was razed in 1929.

In 1904, when he was looking for a location for a country home, W.W. Sylvester, general manager of the Kansas City, Mexico, and Orient Railroad, was attracted to a wooded area at 51st and Wornall. Sylvester chose it, in part, for its fine grove of walnut trees. It stood far away from the hustle and bustle of downtown Kansas City, the perfect place for a restful retreat.

Sylvester built a large stone mansion on the site around 1909. However, the home became better known to Kansas City’s elite a few years later when Wallace N. Robinson’s family moved in. Mrs. Robinson was a musician and enjoyed entertaining, and the house offered the perfect venue. It had a pipe organ at the end of a great hall, and a landing above held an orchestra pit. The third floor was a ballroom.

The Kansas City Star reported on Dec. 19, 1919 that the Robinsons opened home for “revival of the old neighborhood custom of Christmas carol singing. There are to be twenty-eight singers, directed by Allen Hinckley. The rooms will be lighted in the old way with candles, and the singers will be concealed in the shadows. Powell Weaver will play the organ, which is in the middle of the landing in the large reception hall. The ballroom will be opened as an auditorium, and the lower floor reserved for latecomers.”

The next owner of the mansion many have valued the entertainment space as well but also foresaw the future potential. James McNamara bought the home in 1922 for $100,000. He intended to live there initially, but McNamara, who owned lots of land, and his son-in-law, Roy Collins, who controlled the company that owned the Woodlea residential hotel near 36th and Broadway, saw the site’s great potential as a luxury apartment site.

Stage is Set for Kansas City’s Most Elite Development

For several reasons, the site at 51st and Wornall morphed from the perfect country home location to the best position for a luxury residential hotel. Development pressure, which saw huge mansions on Armour Boulevard torn down to make room for tall apartments, moved south of Brush Creek after 1920. Wealthy families, frustrated by the difficulties of finding and retaining servants to run their homes, flocked to the new apartment hotels that required smaller support staff. The city was encouraging high-rise development south of the plaza through its zoning codes. Finally, Mrs. Jacob Loose had recently donated 80 acres diagonally across the street to be known as Loose Park.

So when the Walnuts mansion went on the market, a builder named W.F. Coen didn’t hesitate – in fact, didn’t even look at the inside of the home – before buying the ten-acre property. He envisioned “groupings of high-class apartments on the site,” and real estate experts predicted new residential units there could compete with the Park Lane, Bellerive, and other apartment hotels.

But it was another developer, C.O. Jones, who hatched the grand plan for Kansas City’s most high-end apartments and nearly lost his fortune in the process.

His original vision was 54 units that would compete with anything on the East Coast. “The structure will introduce to Kansas City duplex apartments, with 2-story living rooms in English treatment with heavy oak beams and rafters, as well as studio apartments,” he told the Star on Feb. 5, 1928. He planned to build two tall buildings with apartments as large as sixteen rooms, with a ground floor consisting of lobbies, parlors, a valet kitchen, a large assembly room, and additional special quarters for chauffeurs and maids not housed in the apartments.

He also wanted to introduce another new trend—rooftop garden apartments or penthouses. Composer George Gershwin had just moved into such an apartment in New York to much ado. Jones said he would turn the top tenth-floor apartments into such rooftop gardens.

Another unusual feature was the proposed development’s ownership. Jones wanted the buildings to be co-operatively owned by the families who lived there. However, the co-operative model proved hard to manage and was dropped in 1933.

As building got underway, the number of units was reduced to 42, with three buildings making up the new Walnuts.

Well-to-Do Families Flock to the Walnuts

Jones apparently had a good idea because his proposed apartments began to sell. The first to buy was Theodore Gray Gary, the wealthy owner of the Macon Telephone Company in Macon, Missouri. Other elite families followed and, to Jones’ surprise, often requested that two of the large units be combined. Late in 1929, Mrs. Jacob Loose bought the most expensive apartment, giving up her four-story mansion on Armour Boulevard to move into an entire floor of the Walnuts overlooking Loose Park.

By early 1930, Jones had sold 30 units for more than a million dollars. He razed the old mansion and set up a concrete mixing plant on the site to start construction. But in the fall, Jones became ill with jaundice and also suffered setbacks making payroll during a time when credit was hard to get. But the wealthy owners stepped up and worked out problems, using their influence to get the project finished.

As construction on the outside resumed, owners completed their interior finishes based on their own taste. They often brought items from their old mansions, such as the Tiffany doors one resident had installed. Several suits had master bedrooms with two baths, something previously unheard of even in Kansas City’s fanciest buildings.

Jones aggressively marketed the Walnuts that year, with advertisements like this in the Kansas City Star on Nov. 16, 1930.

The Walnuts particularly appeals to home seekers. But the many additional hotel-like advantages cannot be overlooked in your consideration of modern conveniences. The following are a few of the advantages to be had in a Walnuts residence: a complete staff of attendants, garage facilities, telephone and elevator service, large lawns, formal gardens, and the finest meals served through an exclusive Walnuts’ system.

The garage, providing two spaces for each apartment and four spaces for the double units, was built underground and was the second largest garage in Kansas City when completed (only one at 19th and Broadway topped it in size).

A rooftop view from the Walnuts (date unknown).

“The Walnuts” Spawns “The Peanuts”

The reputation of the Walnuts as Kansas City’s toniest address continued for decades. In fact, according to the Star in 1940, “Residents on the opposite side of Wyandotte adopted the term ‘The Peanuts” for their less pretentious apartments, and soon a neighborhood tavern was flourishing under that name at a nearby Main Street corner.”

Historic photos courtesy Kansas City Public Library/Missouri Valley Special Collections and The Kansas City Star.

I love stories of old KC. This was very interesting. Mrs. Jacob Loose’s 4 story mansion on Armour Blvd. was mentioned – more on this, please.

When I rented an apartment in a house on Central, where the Walnuts residents could look down on the block, the house owner told me that Hall family matriarch lived on the top two floors of one of the Walnuts, and that she single-handedly prevented the city from allowing developers to raze the homes on Central, between 49th and 50th, to make way for new condominiums. I recently visited Kansas City, in 2017, and was not surprised to see that the houses on that beautiful tree-lined stretch of Central were gone. What I want to know is, is there any truth to any part of the story that I was told?