4425 Terrace today, viewed from the west. Captured March 2025.

Like most American cities, Kansas City suffered a lull of private home-building throughout the decade of the 1930s. Outside of the impressive public construction projects associated with the Ten-Year Plan, a scant few neighborhoods saw extensive development during this period, and many commercial and industrial buildings of the era are defined by their functional orientation and simple design. The more notable examples exhibit curved storefronts, rounded windows, and creative use of block glass, characteristic features of Streamline Moderne styling. Only a handful of standout private residences dared to adapt this definitively modern design methodology to established Kansas City neighborhoods, however, and none have achieved the notoriety and recognition of the Walter Bixby House, a National Register individually-listed mansion along the Missouri side of State Line Road and West 65th Street. Tucked just south of Westport Rd. on Terrace Street, however, is another equally distinctive Moderne home with its own compelling story.

Completed in 1938, the Emil Rohrer home at 4425 Terrace Street holds a place in local history as a custom-built residence inextricably linked to the personality and professional aspirations of its original owner. Emil J. Rohrer, a local cement contractor and businessman of the building trade, will be forever memorialized by this innovative application of concrete in residential construction. His relatively short career as a construction executive led him to interface with some of the region’s major projects before his death at the age of 46.

The German-speaking Rohrer family immigrated from Switzerland in 1913 or 1914 (depending on the source). Not-yet-teenage Emil, his mother, and his two siblings seem to have followed his father, whose naturalization dates to 1905, according to census records.

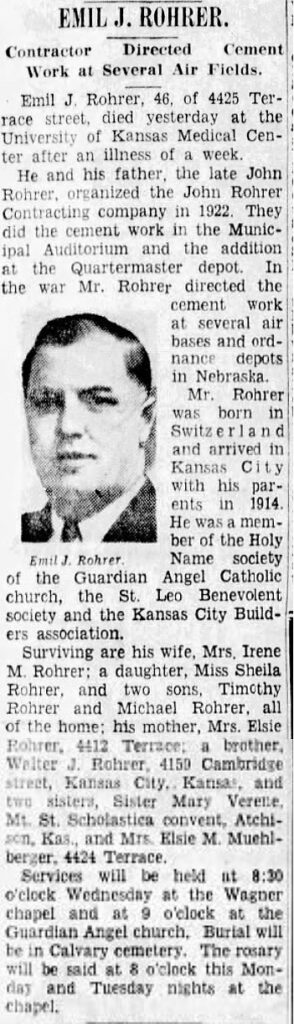

In 1922, Emil and his father John co-founded the John Rohrer Contracting company.[1] They performed contracting work for cement components of Municipal Auditorium and the addition to the Quartermaster depot in Kansas City. During the Second World War, Emil “directed the cement works at several air bases and ordnance depots in Nebraska.” He was an active member of the Builder’s Association of Kansas City, serving as its treasurer beginning in 1943, and was mentioned in news reports as a representative of “cement finishing contractors” in gatherings involving building trades groups.[2] In any case, while city directory records in the mid-1930s show nearly three dozen listings for concrete contractors, it seems clear that Emil had risen to the top of his field. (Photo to the left: Obituary of Emil Rohrer from an August 2nd, 1948 issue of the Kansas City Times. Pg. 11.)

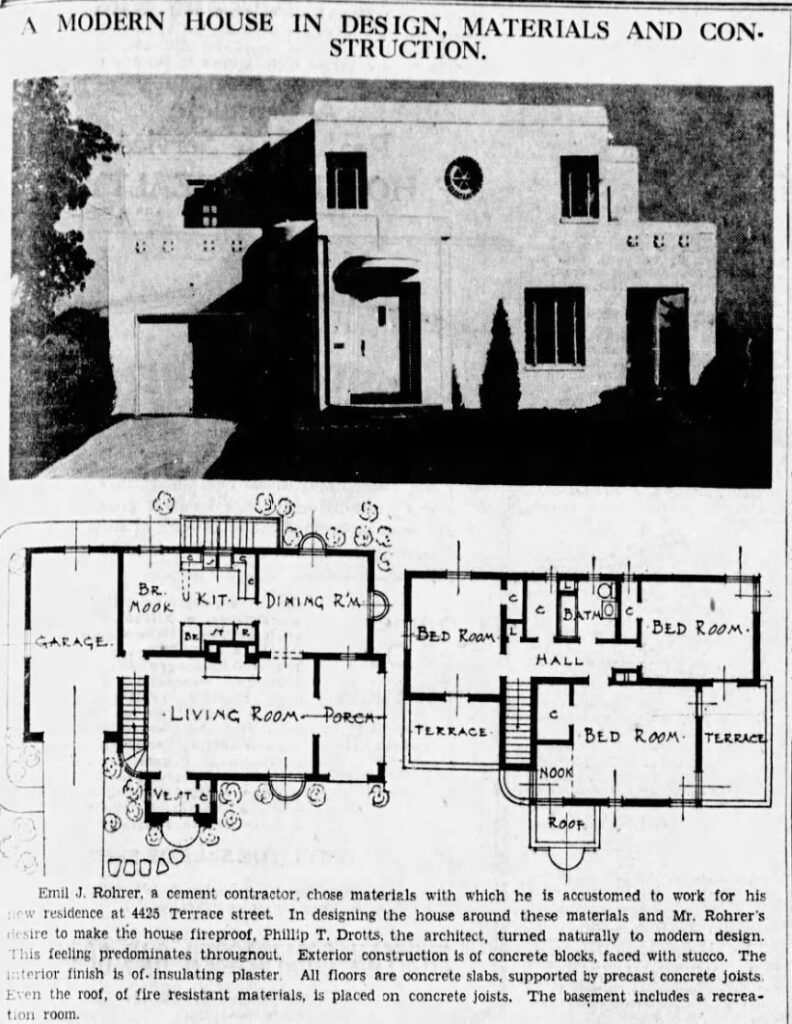

Concurrent with his rise to prominence in the local business community, Emil built the house at 4425 Terrace Street as a home for his family—his wife, daughter, and two sons. The house was designed as a compact configuration of three bedrooms, a living room, and dining room, and a single bathroom–augmented by a breakfast nook adjoining the kitchen, a garage within the northern end of the first floor’s footprint, a first-floor porch, and two second-floor terraces accessible through each of the upstairs bedrooms.

Distinctive features of the home as pictured in a 1938 Sunday issue of the Kansas City Star include a slightly offset, centrally located entrance along the west-facing elevation (facing Terrace Street) covered with a flat, rounded canopy. (Clipping above: Photograph and plans for Emil Rohrer’s newly-built home, from a Sunday, October 30th, 1938 issue of the Kansas City Star. Pg. 5D.)

Just adjacent to this entrance, though obscured by shadow in the newspaper image, is the sole staircase for interior circulation. It is illuminated on the first story by a curved wall of block glass that abuts the lowest few stairs. Windows line the corners of upstairs bedrooms, and a small porthole window sits centered in the primary elevation’s second floor. Perforations in the upper-floor terraces resemble a pattern of breeze blocks. (Photos above: Interior and exterior views of Moderne ‘turret’ staircase rising from first floor, showing curved wall surface of block glass. Captured March 2025.)

The Star photo was accompanied by the following caption, which emphasizes Rohrer’s choice of building material:

Emil J. Rohrer, a cement contractor, chose materials with which he is accustomed to work for his new residence at 4425 Terrace street. In designing the house around these materials and Mr. Rohrer’s desire to make the house fireproof, Phillip T. Drotts, the architect, turned naturally to modern design. This feeling predominates throughout. Exterior construction is of concrete blocks, faced with stucco. The interior finish is of insulating plaster. All floors are concrete slabs, supported by precast concrete joists. Even the roof, of fire-resistant materials, is placed on concrete joists. The basement includes a recreation room.

That the newspaper caption reads like an advertisement is not surprising, given Rohrer’s interest in spreading awareness of concrete’s applicable uses in single-family residential construction. It is his commitment to sporting his own product that registers as most remarkable, insisting on poured concrete floors atop concrete joists on each floor. Also notable is the owner’s recruitment of Phillip Drotts, a well-known Kansas City architect, to design the home despite what must have been onerous–even experimental–design prescriptions. By the late 1930s, Drotts had a good number of impressive buildings to his name: churches like Broadway Baptist Church at 3931 Washington Street and apartment hotels like the Newbern Apartments at 523 East Armour Boulevard. He was listed as architect for only one definitively Moderne project prior to 1938, erecting a commercial strip at 4800-06 Belleview Avenue just the year before. Insofar as later observers recall, the 4425 Terrace Street became the most notable design commission he produced for a private home.[3]

Was this construction unique among its contemporary Moderne-style houses of Kansas City? At least seven area homes were built within the decade and a half surrounding Emil’s concrete experiment, according to a 1989 Art Deco Survey of Kansas City, Missouri and available records from the Kansas side. Each of these homes exhibit aspects of Moderne style, though most lack a strong association with streamlined aesthetics. These include, in addition to the Rohrer house, include the Walter Bixby home at 6505 State Line (1935-1937), 5044 Summit (1935-1936), 425 W Meyer Blvd. (1937), 1152 E 78th St. (1939), and 8425 Mercier St. (1949), and the John Verbanic House of 1823 Washington Blvd. in Kansas City, Kansas’ Westheight Neighborhood.

The home at 4425 Terrace, viewed from the south, showing pergola and porch additions. Captured March 2025.

And why did Rohrer seek to build his two-story concrete castle at 44th and Terrace? Terrace St., just south of Westport Rd., remains today largely as it had been then: a row of modest bungalows tucked away from the major east-west and north-south thoroughfares. A look through census records, however, shows how the Rohrer family anchored themselves along this single block of Terrace St., with all family members shown in residence at 4412 or 4408 Terrace St. from the 1910s through the 1940s, though there is some indication Emil might have relocated a few blocks south before occupying 4425 Terrace St. Emil and his family were also long-term parishioners at Guardian Angels Catholic Church just up the road—visible, indeed, rising above the end of Terrace St. looking northwards. As the center of Kansas City’s German Catholic community during these heady decades of the early 20th-century, the family was in company of many German language-speakers along neighbors and fellow parishioners, even after the congregation deliberately shed its outward markers of ethnic association in the midst of wartime uneasiness in 1917-1918. Emil’s sister, Clara—later Sister Mary Verene—joined the Benedictine Order, and Emil’s name is memorialized in one of Guardian Angels’ grandiose stained glass windows.

The family did not leave their house behind immediately after Emil’s death, as wife Irene and children Sheila, Timothy, and Michael are shown residing there in 1950. The property itself has seen few changes since; the garage was converted to an interior room and a side porch was expanded on the south side with the addition of a pergola-type covering. As of this writing, the house is listed for sale.

[1] Obituary of Emil Rohrer from an August 2nd, 1948 issue of The Kansas City Times. Pg. 11.

[2] “Into Cost of Building,” The Kansas City Times, November 13th, 1947. Pg. 1.

[3] Sherry Piland, “A Kansas City Architect: Phillip Drotts,” Historic Kansas City Foundation Gazette 7 (July/August 1983)

Emil Rohrer was my gradfather. Died well before I was born. My dad, Tim Rohrer, Sr. was one of his sons and later led John Rohrer Contracting after his uncle Walter Rohrer retired. I remember visiting my grandma in that house most Saturdays when I was very young. Thank you for recognizing this part of KC history!