Do you ever get that deja vu feeling while traveling around Kansas City? If you’ve ever stopped for a double-take after after thinking, “I’ve seen this before,” you might recognize one distinctive building type either tucked away along quiet, park-side boulevards. Those who remember the now lost neighborhoods of Midtown might also recall the Tudor 12-plex building design highlighted in this article.

Even as constituent neighborhoods of the urban core are defined by their diversity, similarities abound among much of the city’s residential architecture. It can be positively disorienting to see what appear to be examples of the same building type—but in two different locations—as if prompted by a command of “copy-and-paste.” Yet, upon inspection, this phenomenon is frequent across century-old neighborhoods of Kansas City. The sturdy-looking Tudor 12-unit apartment building design explored in this article, distributed across Midtown Kansas City, helps transport us back to a place in time when stylistic taste, changing zoning codes, and eager developers shaped our cityscape in dramatic fashion.

The years following the First World War was an era of prolific construction of apartment buildings. The decade from 1920-1929, for example, brought “15,152 new apartment units and 1,092 new duplex housing units” onto the market, with 1923 marking the most fruitful year for construction.1 Architectural historian Salley Schwenk summarized the densification of midtown in the 1920s by noting that “both the number of smaller units and large apartment buildings (eighteen to twenty-four units) appeared in clusters in different neighborhoods, establishing apartment housing as a significant part of the City’s residential patterns.”2 Increasingly, developers took on the role of ‘master planner’ for a series of adjacent apartment buildings.

Guy McCanles began his career as a builder erecting single-family homes in Kansas City, before shifting to apartment buildings in the early 1910s, in partnership with Roy Gregg, who managed sales, rentals, and exchanges. By the time of Gregg’s death in 1920, McCanles stood alongside only developer Charles Phillips (known for being the employer of Nelle Peters) as the most prolific of apartment developers; this legacy was reinforced in the following years with founding of the McCanles-Miller Realty Company, incorporating salesman George W. Miller. The McCanles-Miller business model in the following years was simple: arrange cohesive developments in strategic areas of the city center, construct the maximum number of apartment buildings with the greatest allowable unit density, and sell individual buildings once developments near completion. Revenues were then invested in new, larger projects, creating a feedback loop of ever-increasing scale of development.

The environmental circumstances influencing the McCanles Company’s rush to build cannot be addressed in full in this article. Suffice it to say that, amid an onset of zoning restrictions prohibiting apartment buildings in many locations and new building codes requiring fire-proof materials, Guy McCanles joined other builders racing to construct apartment complexes in the early 1920s.

Two of those buildings, pictured atop this article, filled in empty lots adjacent to five McCanles-developed six-plexes from 1917, located along Valentine Road just west of Mercier Street. Built in 1923, these two 12-unit buildings employed near-identical designs 1301-1303 and 1305-1307 Valentine Road, respectively.

The Manchester and Ipswich are both clad in brick on all elevations of their three stories, with foundations of natural stone stacked in thin layers. Front elevations employ cast stone for buttresses and tympanum panels framing entry portals. Just a few elements combine to convey Tudor styling (of the no wood variety, lacking the half-timbering and stucco familiar to most). Decorative cast stone elements are found in the parapet walls along the roofline, with simple shield motifs flanked by small pilasters resembling balusters, all situated below cast stone coping. These buildings are differentiated only by brick patterns in spandrel panels and arched configurations of some window openings.

These are but two of five known iterations of this same building design; at least four additional uses of the building design for 12-unit configuration can be confirmed. One 12-unit building, the “Dorchester,” is located in the Southmoreland neighborhood at 506-508 E. 44th Street. It sits just south of a truncated six-unit variant of the design facing east onto Rockhill Road.

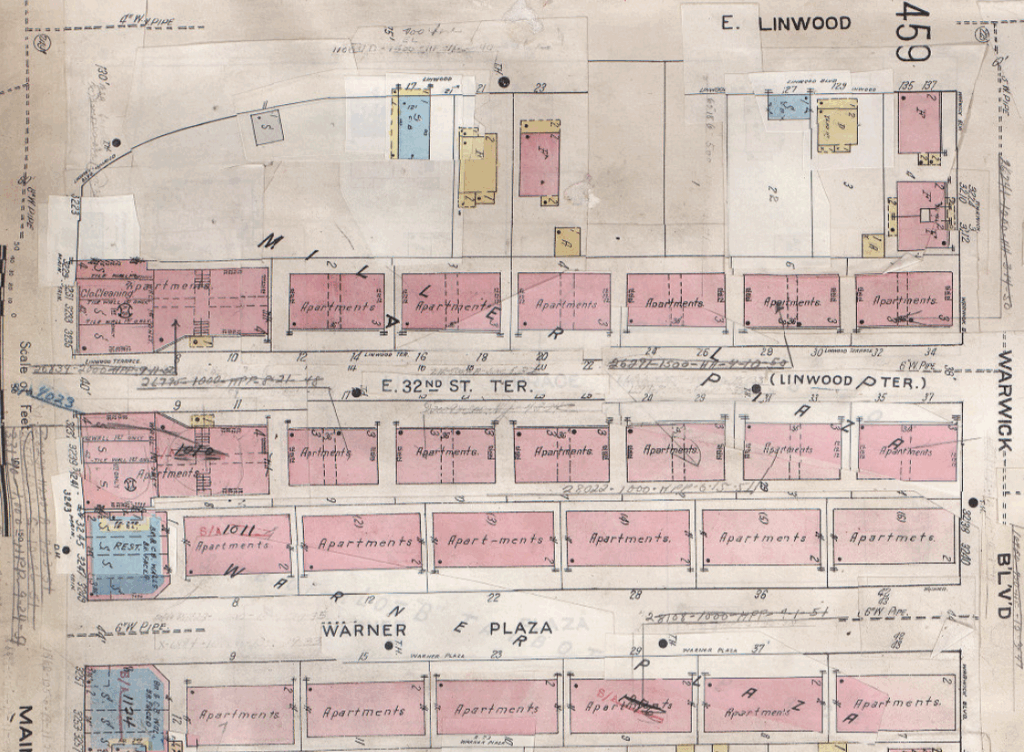

Southeast of Linwood and Main, atop what today serves as the parking lot for Home Depot, was one of McCanles’ largest-ever developments. Undertaken in 1923 by the McCanles-Miller Company (though named for the previous occupants of the tract, not the business partner), Miller Plaza was a tightly concentrated development of three-story apartment buildings on either side of a single street proceeding from Main to Warwick. It featured twelve twelve-unit buildings, all of which followed one of just a few building templates. Three of the buildings exhibited the Tudor design, with near-identical details to the above examples. Design for all buildings was credited to Frank Brockway, the construction supervisor for the McCanles Company. The complex was joined in the following two years by Warner Plaza, a McCanles and Brockway-supervised project immediately to the south.

The story of Miller Plaza and Warner Plaza was one of dense urban living and, as the century wore on, declining stewardship. Redevelopment proposals saw demolition of the complex as a necessary means to address the crime-ridden and largely vacant buildings. All that remains of the Miller Plaza development are distant memories and a few photographs; not one physical remnant survived the excavation for the big-box store parking lot. The Historic American Buildings Survey managed to capture a few final snapshots in 1986 just before their demolition.

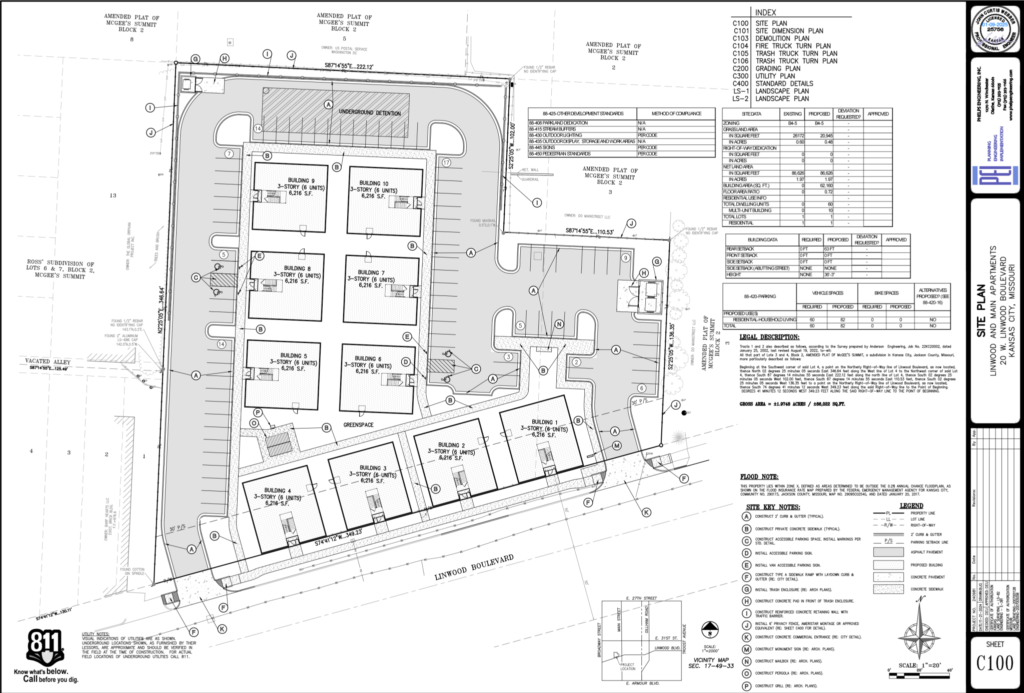

Thus, instead of six examples of this repeated building design, we are left with only a trio of survivors. Thankfully, the Dorchester of the Southmoreland neighborhood has already attained recognition on Kansas City’s local historic register, introducing protections against demolition and design review for exterior building changes; it has also experienced split ownership as a condominium complex. The two examples on Valentine Road, meanwhile, are set to attain recognition on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Whiteside Place No. 3 Historic District, named for a property owner of the tract preceding Guy McCanles. Even as the remaining examples remain, the erasure of Miller Plaza serves as a compelling reminder that Kansas City’s historic, affordable housing stock—a bedrock of our local built environment—has suffered from unsustainable attrition in recent decades. Indeed, the acute shortage of housing now experienced by the vicinity of Miller Plaza’s successor parking lot has prompted proposals from VanTrust Real Estate, in partnership with Driven Development, to build 10 adjacent six-unit buildings, each identical to the next, as part of an effort to repopulate this city-center location. It just so happens that this development site, catty-corner to that of Miller Plaza, will require ample city investment to create just a fraction of the housing units lost from the demise of the McCanles Company’s twin developments.

Sample elevations and site plan from a proposal to build 10 adjacent six-unit buildings northwest of Linwood and Broadway. Image sourced from BZA records, dated 6/6/2025.

Historic buildings don’t need to be unique, or “high-style” to deserve recognition. Preservation tools like historic designation are sometimes all that stands between serviceable apartment buildings being consigned to the wrecking ball as just another fragment in Midtown’s rubble heap of lost neighborhoods. Indeed, only when our community recognizes the contributions of these particular building types to Kansas City’s story do we begin to articulate the reasons for preservation. The mere fact of a building type having been copy-and-pasted ought not consign it to oblivion or obscurity, just as a building’s age need not condemn it to demolition. We ought to make room for recognition of these ‘common’ property types, whether on ‘honor rolls’ like the National Register or simply regarding them as equivalent in significance to many of the grand homes that stand alongside them. Most of all, the continued abundance of examples of copy-and-paste apartment buildings of the 1910s and 1920s should prompt reflection on the historical phenomena that enabled their surroundings to grow into the Kansas City we know and love today.

The above article is partly excerpted from a Jackson County Historical Society E-Journal article entitled “Copy-and-Paste Architecture: Recognizing Repeated Patterns in Kansas City’s Built Landscape,” written by Ethan Starr and published June 30th, 2025. It can be accessed through the following link: https://www.jchs.org/jchs-e-journal/copy-and-paste-architecture. Other similar articles on Midtown KC Post can be found under the tag Buildings and Architecture.

Mary Jo. I loved this! Thanks!

Credit goes to Ethan Starr, but thanks, LaDene.