Do you ever get that deja vu feeling while traveling around Kansas City? If a familiar-looking apartment building prompts you to stop and do a double-take, there’s a decent chance it’s an example of what we call the “prolific six-plex.” Even as constituent neighborhoods of the urban core are defined by their diversity, similarities abound among much of the city’s residential architecture. It can be positively disorienting to see what appear to be examples of the same building type—but in two different locations—as if prompted by a command of “copy-and-paste.” Yet, upon inspection, this phenomenon is frequent across century-old neighborhoods of Kansas City. Of all the many repeated building patterns present in our area, one stands above the rest as so prolific, so numerous, that it can be found across Midtown, Northeast, and East Side neighborhoods of Kansas City.

This particular building type is examined in great detail below, but we must first turn to consider what is meant by “repeated patterns” or “copy-and-paste.” Repetition occurs when multiple buildings share common features of massing, material, and decoration. But what about similarities that do more than conform to a generalized type? This article considers more extreme examples of pattern repetition as they relate to a particular type of six-unit building. The examples cited below demonstrate a phenomenon which could be aptly called “copy-and-paste.” This analysis should help locals to re-define the familiar aspects of their surroundings as distinguished contributors to our city’s building stock, as well as a direct consequence of yesterday’s decisions.

Kansas City was building in all sorts of ways in the early 20th-century, but it was residential apartment buildings that best exemplify “copy-and-paste” design schemes. These buildings were constructed for a working- and middle-class clientele, a population for which urban housing demand picked up steam following the First World War. This was an era of prolific builders catering to a pent-up demand for housing. The decade from 1920-1929, for example, brought “15,152 new apartment units and 1,092 new duplex housing units” onto the market, with 1923 marking the most fruitful year for construction. Increasingly, new units arrived in more creative and diverse configurations than before, with ‘apartment courts’ and ‘apartment hotels’ joining the more standard walk-up ‘flats.’ The surge of apartment construction did not amount to an increase in the rate of building over pre-war years, but the typical unit count expanded over the years from six to upwards of 18 per building. Colonnaded apartments, deservedly, receive much of the attention from this era.1 But what of the more self-contained, small-scale apartment buildings—the type that preceded the ‘scaling-up’ of unit count in the 1920s?

Before it became vogue to build tall—either ‘mid-rise,’ at five to eight stories, or high rise, at eight or more—maximizing economization lot square footage and interior space was best accomplished by tightly spacing a series of similarly formulaic apartment ‘flats.’ Construction of these more self-contained ‘walk-up’ three-floor buildings (relatively ‘low-rise’) accelerated in the 1910s as the population outside of Downtown increased dramatically, with streetcars creating easy transportation access to a host of new neighborhoods made eligible to house working-class residents. Historian Sally Schwenk, who wrote an extensive report in 2007 studying “Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri” also notes the “advent of new building codes that mandated indoor plumbing facilities and dictated minimum window exposures and maximum lot coverage” as design parameters influencing the erection of buildings historians labelled as comprising the “Low-Rise Walk-Up Apartment Building Sub-Type.”2

As the name suggests, these buildings were best described as rising to three or fewer stories and walk-up access; they were also characterized by an absence of elevators and lobbies, as well as straight, L-shaped, or T-shaped double-loaded corridors. Crucially, these formulaic structures—keeping true to the aphorism that form ought to follow function—aimed toward maximum efficiency, and they were also less expensive to construct. Like their colonnaded brethren, most of the low-rise, boxy ‘flats’ wore brick cladding as a garment atop a wood frame skeleton. Not until the introduction of strict fire codes in 1924 did concrete construction become the standard.3

Exterior cladding provided a canvas for designers, and some made good use of the opportunity. Flashy building ornamentation—terra cotta portals, column capitals, and dentilled cornices—were used sparingly, but in highly visible areas, connoting association with the Old World charm of a revival style. Alternatively, the building components could themselves be manipulated to convey a sense of distinction, like bricks arranged to create a tapestry effect or wood spandrel panels bearing an applique design. Stone sills and wide eaves were often combined to emphasize horizontality in the manner of the Prairie Style. In the words of architectural historian Sally Schwenk, “Many architects experimented with fanciful combinations of these styles, often featuring an intentional combination of stylistic treatments and, as a result, residential designs no longer fitting neatly into stylistic categories.” The outcomes of these competing decorative methodologies were a hodgepodge of stylistic motifs, ornamental panels, or brackets conveying Revival styles of choice—employing Classical or Colonial, or turning to Tudor as the decade drew on—alongside an ever-more modern expression of building form as following function.

One grouping of 1920s six-unit buildings that exemplify the “Low-Rise Walk-Up Apartment Building” typology can be found on Valentine Road just south of Roanoke Park, arrayed diagonally on the block bound by Terrace and Mercier Streets. Five buildings along Valentine Road and Terrace Street are fashioned with slight variations of a Classical Revival idiom with distinct Craftsman and Prairie Style influences. These five buildings employ a somewhat variegated, textured brick in their facades in tapestry-like patterns, with the most visible exterior ornamentation conveyed via applied wood elements. Differentiated mostly through deployment of the wooden decorative ornaments, their designers maximized the use of an efficient massing and ease for reproduction across multiple iterations. Their eaves and panels of applied wood ornament, in particular, reference both the wide overhangs and horizontal emphasis of Prairie aesthetics, albeit transmitted alongside traditional decorative elements of an entablature and dentilled cornice. Details like bracketing under eaves and patterned spandrel panels were a commonplace mechanism for adding some extra pizazz while avoiding the added expense of rendering designs through masonry. Like many apartment ‘flats’ of this type, brick cladding covered the majority of the exterior, while builders utilized a lesser material for cladding rear elevations. The potential of cost savings seems a clear motivation for this material and stylistic disparity of front and rear. The economization of resources also highlights the importance of presenting the best of ‘appearances’ toward the public, street-facing elevation—in the case of these five buildings, directly overlooking Roanoke Park—as a factor prioritized over uniformly sheathing the totality of a facade in brick.

Given the profound efficiency of this particular design, it seems intuitive that builders would have sought to replicate it elsewhere. Other applications of the near-identical building plans can be found just a quarter-mile away on Genessee Street or West 39th Street. Just a few blocks further south, still in the Volker neighborhood, a trio of the same six-unit design occupy the southeast corner of 41st and Mercier Streets. As a reader, if you’re racking your brains trying to remember just where you might have spotted one (or several) of these buildings across Kansas City, have a look at the table at the bottom of this article to peruse the 52 known examples and find which is most familiar to you.

This scale of architectural copy-and-paste is staggering, even for the early 20th Century dawn of mass production. Granted, this level of repetition might not have been out of step with broader trends in the house-building trade, considering Kansas City’s rapid pace of expansion in the 1910s and 1920s and its relatively small cohort of housing developers. South Kansas City residents might recognize the name Napoleon Dible, who built 4,000-5,000 homes, including a vast number of Tudor ‘kit’-type houses using techniques of mass production and, accordingly, repetition on the inside and outside. Surely, among the 4,000 or so Dible homes still at large, at least a few favorite patterns are now represented by dozens of examples?

Many more clusters of buildings can be identified as broadly resembling the aforementioned six-unit apartment buildings (arrayed in a quintet along Valentine Road and Terrace Street, overlooking Roanoke Park from the south). Think of the apartment court and adjacent buildings along Summit Street (Southwest Trafficway) just north of 37th Street and included within the Nelle Peters thematic Certified Local District (Figure 9); they share many basic features with the repeated design examined here. Yet, can that not be said of most any boxy, three-story, walk-up building?

Yet, for someone who encounters clusters of this same building design in different locations—not just Valentine Road and Terrace, but Mercier Avenue and 41st Streets (three buildings), 30th and McGee Streets (five buildings), and the vicinity of 27th Street and Benton Boulevard (five extant buildings), it becomes clear just how widely the methodology of copy-and-paste spread this singular design. You will notice that all these examples employ wood applique motifs of arrows and rectangles on spandrel panels (adjoining windows in the area between stories). These motifs appear to alternate from building-to-building, just as front entryways might sport either triangular pediments or rounded tops, creating a sense of variety amidst near-identical repetition of most other features. It is also noteworthy that some of these buildings occur individually among clusters of other apartment designs—including not only similarly ornamented colonnades, but also a version of the aforementioned ‘boxy’ design with projected bays on either side of the front entrance in a way that resembles the massing of a colonnaded building. By making an inventory of these three-story, walk-up buildings across the city and examining in closer detail their distinguishing ornamental features, we can identify distinct designs and patterns of repetition that bely a more comprehensive building scheme of which any individual building or cluster is only a small piece.

The table of 52 buildings at the foot of this article provides as complete an inventory as could be assembled by the author, compiling photographs of extant buildings, records of known examples attested by 1940 tax assessment photographs, and supplementary data from architectural surveys and various district nominations for the National Register of Historic Places. The McCanles Realty Company is responsible for the great majority of those examples with easily accessible information pertaining to the original builders. If indeed the design’s proliferation is owed mostly to the McCanles Company, one wonders how the boxy, ornamented design discussed above gained favor to the point of outnumbering all the other repeated apartments designs utilized by the firm. The origins of the design remain mysterious, however; no architect is listed for any of the buildings, according to records reviewed prior to the writing of this article. At least one example, 3634-3636 Forest Ave. in the Squier Park neighborhood and National Register District, is attributable to Napoleon Dible of the Home Investment Company, the prolific developer of working-class, single-family housing city-wide mentioned above.

Despite recognition of a handful of these buildings on the National Register of Historic Places (which, heretofore, has been largely incidental, a result of the neighborhoods around them gaining recognition), examples of our prolific six-plex remain very much threatened by neglect and at risk of disappearing as an affordable housing resource of the future. As an illustration of the longstanding threat of demolition for these historically significant, if much-repeated, building types, let us turn back to the full inventory of the repeated boxy, three-story, walk-up design so favored by Guy McCanles and others, which includes examples identifiable only by historic imagery. Of the 52 known examples to have existed—which is very likely an underestimate—12 have been demolished since 1940.

Barring the occasional fire or small-scale disaster, demolitions of these historic apartment buildings tend to take place simply when owners neglect needed reinvestment, a community ceases to pay attention, or when the public does not deem it to hold any particular historic significance. This is, after all, why the National Park Service refers to the National Register of Historic Places simply as a “official list of the Nation’s historic places worthy of preservation.”4 Only when our community recognizes the contributions of particular buildings or building types to Kansas City’s story do we begin to articulate the reasons for preservation. The mere fact of a building type having been copy-and-pasted ought not consign it to oblivion or obscurity, just as a building’s age need not condemn it to demolition. We ought to make room for recognition of these ‘common’ property types, whether on ‘honor rolls’ like the National Register or simply regarding them as equivalent in significance to many of the grand homes that stand alongside them. Most of all, the continued abundance of examples of copy-and-paste apartment buildings of the 1910s and 1920s should prompt reflection on the historical phenomena that enabled their surroundings to grow into the Kansas City we know and love today.

Table 1. Below is a table of 52 known examples of the boxy, six-unit typology associated with the activities of the McCanles Realty Company in the latter 1910s. Classifying dozens of examples of this building typology—both extant and demolished—required adoption of certain necessary criteria for inclusion. These included basic organization of window openings—paired windows in central bays being flanked by tripartite configurations—as well as more basic characteristics like three-story height, brick facade atop frame construction, and extension of brick only to three building elevations. Cornices and entry portals were subject to variation and did not serve as factors of exclusion. At least one pair of wooden spandrels (usually decorated with applied wood ornament of arrow or rectangle motifs) was required for inclusion in this cohort.

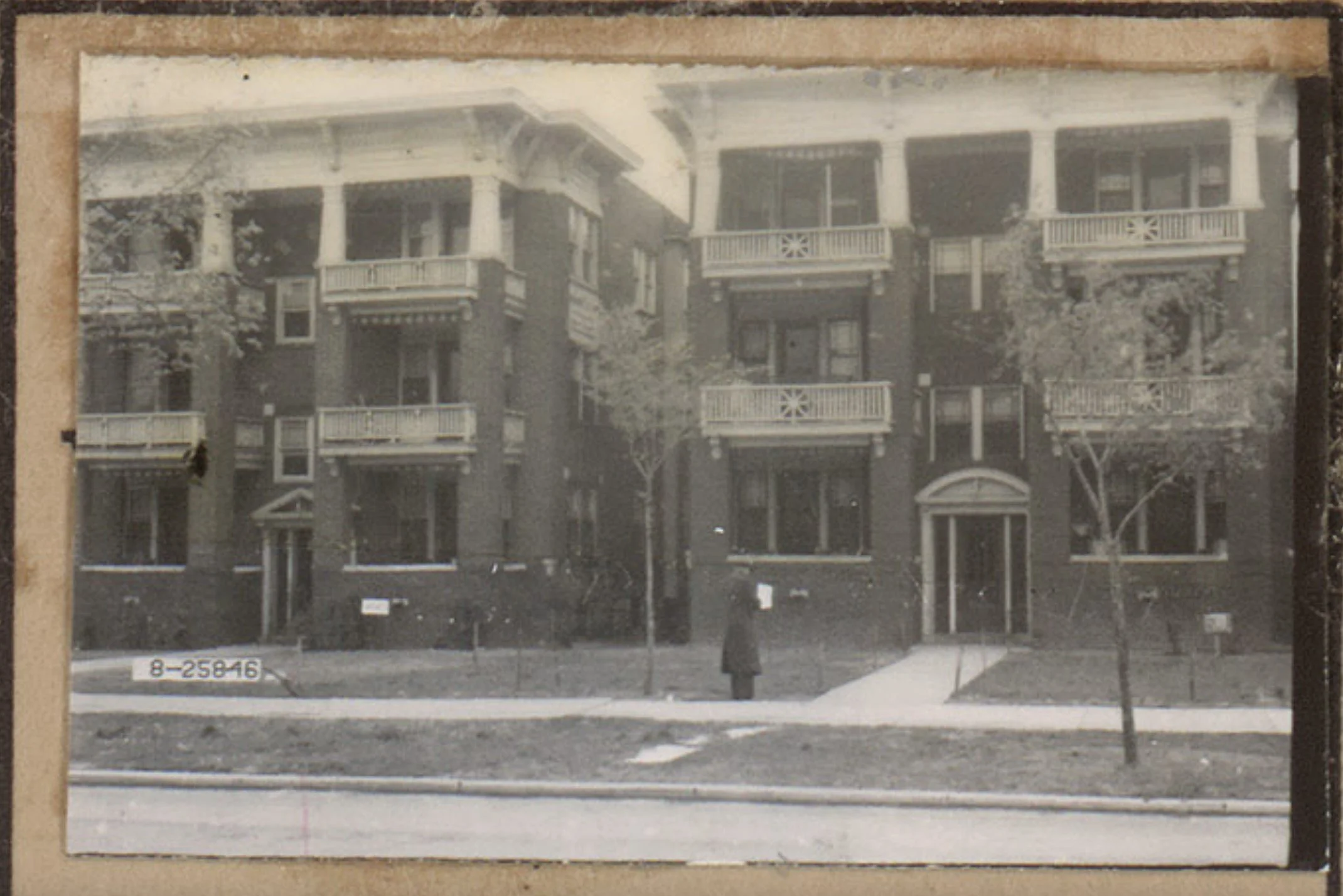

| # | Address, Date | 1940 Tax Assessment Photo | Contemporary Photo |

| 1 | 1311-1313 Valentine Rd. 1917 McCanles Realty Co. Whiteside Place No. 3 (District in progress) | ||

| 2 | 1315-1317 Valentine Rd. 1917 McCanles Realty Co. Whiteside Place No. 3 (District in progress) | ||

| 3 | 1319-1321 Valentine Rd. 1917 McCanles Realty Co. Whiteside Place No. 3 (District in progress) | ||

| 4 | 3801-3803 Terrace St. 1917 McCanles Realty Co. Whiteside Place No. 3 (District in progress) | ||

| 5 | 3805-3807 Terrace St. 1917 McCanles Realty Co. Whiteside Place No. 3 (District in progress) | ||

| 6 | 3826-3828 Genessee St. 1917 McCanles Realty Co. | ||

| 7 | 1319-1321 W 39th St. | Demolished c. 2000 | |

| 8 | 1317-1321 W 39th St. | ||

| 9 | 1313-1315 W 39th St. | Demolished c. 2007 | |

| 10 | 3704-3706 Washington St. | ||

| 11 | 2100-2102 E 33rd St | n/a | |

| 12 | 3237-3239 Garfield Ave | n/a | |

| 13 | 3304-3306 Virginia Ave | n/a | |

| 14 | 3300-3302 Virginia Ave | n/a | |

| 15 | 3228-3230 Tracy Ave | n/a | |

| 16 | 2901-2903 E 27th St | Demolished c. early 2000s | |

| 17 | 2905-2907 E 27th St | Demolished c. early 2000s | |

| 18 | 2908-2910 Lockridge Ave | Demolished c. early 2000s | |

| 19 | 2912-2914 Lockridge Ave c. 1917 Santa Fe District | ||

| 20 | 2903-2905 Lockridge Ave | Demolished c. 2000 | |

| 21 | 2716-2718 Benton Blvd | Demolished c. early 1970s | |

| 22 | 2720-2722 Benton Blvd | ||

| 23 | 2724-2726 Benton Blvd | Demolished c. early 2000s | |

| 24 | 2656-2658 Lockridge Ave | ||

| 25 | 2660-2662 Lockridge Ave | ||

| 25 | 3630-3632 Forest Ave | 1940 photo missing from survey sheet. Existence confirmed via historic aerials. | Demolished c. 1990s |

| 26 | 3634-3636 Forest Ave 1917 Home Investment Company, Napoleon Dible Squier Park District | ||

| 27 | 1223-1225 W 41st St | ||

| 28 | 1219-1221 W 41st St | ||

| 29 | 1215-1217 W 41st St | ||

| 30 | 3107 Peery Ave | ||

| 31 | 2501-2503 E 28th St 1915 McCanles Realty Co East Patrol Survey $15,000 | ||

| 32 | 2505-2507 E 28th St | ||

| 33 | 2509-2511 E 28th St | Demolished c. 1970s | |

| 34 | 100-102 N Indiana Ave | ||

| 35 | 104-106 N Indiana Ave | ||

| 36 | 108-110 N Indiana Ave | 1940 image not available; photo of 100-102 N Indiana Ave was used twice in tax assessment survey. | |

| 37 | 3202-3204 E 6th St | ||

| 38 | 3206-3208 E 6th St | Demolished c. 1990s. | |

| 39 | 617-619 Benton Blvd | ||

| 40 | 613-615 Benton Blvd | ||

| 41 | 609-611 Benton Blvd | ||

| 42 | 633-635 Benton Blvd | Individual image not included in 1940 survey. Partial capture shown above. | |

| 43 | 637-639 Benton Blvd | ||

| 44 | 4017-4019 Harrison St 1921 McCanles-Miller Realty Company South Hyde Park $20,000 to build | n/a | |

| 45 | 4016-4018 Troost Ave. | n/a | |

| 46 | 213-215 E 30th St | ||

| 47 | 217-219 E 30th St | ||

| 48 | 221-223 E 30th St | ||

| 49 | 3006-3008 McGee St | ||

| 50 | 3002-3004 McGee St | ||

| 51 | 3813-3815 The Paseo Blvd | Primary 1940 Photo missing. Existence confirmed via historic aerials and partial capture above. | Demolished in early 1980s. |

| 52 | 3817-3819 The Paseo Blvd |

Table 2. As described in the article above, family resemblance to those boxy, six-unit buildings extends beyond just the 52 examples shown above. Below is found just a sampling of the many buildings that, while having features highly indicative of association with the repeated building typology (and often close proximity to examples provided above), their overall appearance is distinct enough to differentiate from the 52 examples above. Their similarities, however, demonstrate just how frequently repetition of design influenced apartment building construction in this era.

| “Close Calls” not included in the above table | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2700-2702 Benton Blvd | Demolished | |

| 2704-2706 Benton Blvd | ||

| 2708-2710 Benton Blvd | ||

| 2739-2741 Benton Blvd | ||

| 3809-3811 The Paseo Blvd | Demolished c. early 1980s | |

| 3813-3815 the Paseo Blvd | Demolished in early 1980s | |

| 3821-3823 The Paseo Blvd | Demolished c. early 1990s | |

| 3825-3827 The Paseo Blvd | ||

| 4004-4006 Warwick Blvd | ||

| 4000-4002 Warwick Blvd | ||

| 115-117 E 40th St | ||

| 1007-1009 E 42nd St | n/a | |

The above article is largely excerpted from a Jackson County Historical Society E-Journal article entitled “Copy-and-Paste Architecture: Recognizing Repeated Patterns in Kansas City’s Built Landscape,” written by Ethan Starr and published June 30th, 2025. It can be accessed through the following link: https://www.jchs.org/jchs-e-journal/copy-and-paste-architecture.

- Colonnaded apartments served as the subject of the initial Midtown KC post companion article to this piece, and they feature most prominently in the Jackson County Historical Society article that serves as the basis for each piece of writing. Other resources include a 2003 Colonnaded Apartments Multiple Property Documentation Form. ↩︎

- Sally Schwenk, “Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri,” Multiple Property Documentation Form, 2007. Section E, Pg. 31. ↩︎

- “Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri,” Section E, Pg. 21. ↩︎

- “National Register of Historic Places,” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/index.htm ↩︎