A new placard has been installed on a 48th St. building located just west of the Country Club Plaza. How might a new sign, simply denoting “708 W 48th St / COTTESBROOK APARTMENTS,” amount to a newsworthy story?

The sign, situated on a (comparatively) sleepy cut-through between the commercial district and Roanoke Parkway, is significant for restoring the historic name to one of West Plaza’s architectural treasures: a Nelle Peters-designed, 18-unit apartment building. Part of an eclectic district of predominantly Revival-style residential buildings, the “Literary Block,” and recognized by Kansas City and the National Park Service, the story of the Cottesbrook Apartments is a worthwhile one and deserves to be told. Thanks to the re-branding, there is no better time to do so than the present.

A three-story brown brick building with stone trim, the Cottesbrook features 18 self-sufficient units. It exemplifies some of the basic characteristics of Kansas City’s multi-family residential building stock constructed during the boom cycle of the 1920s: three-story height, apartments outfitted with kitchenettes, absence of an elevator, and accessibility via a single entrance from the street level. A very useful report from 2007, entitled “Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri,” categorizes these buildings as belonging to a “Low-Rise Walk-Up Apartment Building Sub-Type.”1 This typology, of course, derives its name from the most fundamental characteristics related to a building’s function. It describes basic, functional design orientations—characteristics discernible from the exterior, though unrelated to the eye-catching elements of aesthetic ornament. For interior layouts, most buildings of this type adopt as their central organizing principle a straight, double-loaded corridor, with units opening on either side of a central hallway.

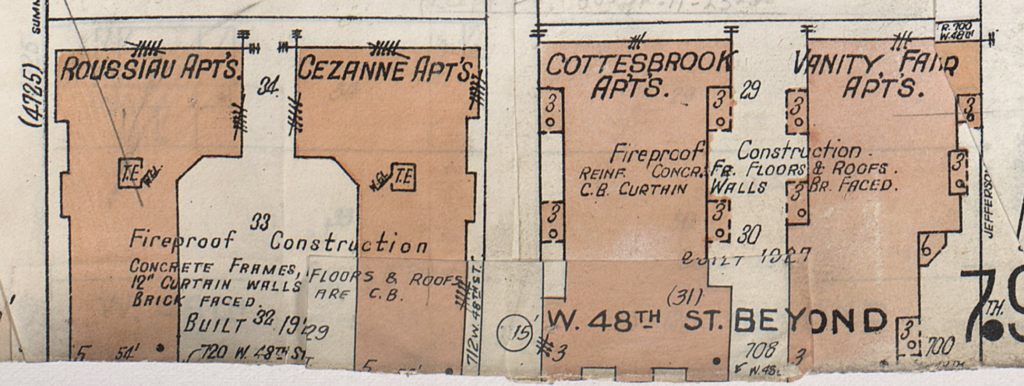

The Cottesbrook is generally rectangular in footprint, resembling somewhat of an I-shape due to its narrowing between the rear and front facades (north and south, respectively). This is punctuated on each side only by the projection of vertically stacked porches to the east and west, creating the effect of a light court on each of those side elevations. As shown by Sanborn maps of the time, the building is of fireproof construction, featuring sturdy reinforced concrete walls and roofs with curtain walls of concrete brick. Importantly, the techniques of construction situate this building beyond that point in time at which exterior masonry was severed from structural functions. This is primarily attributable to new building codes that were instituted in 1924. This less functional exterior sheathing, however, opened avenues to more creative expression. Look no further than the helter-skelter basketweave masonry of the adjacent David Copperfield building, at 804 W 48th St., for proof of concept.

The Cottesbrook’s most distinctive elements are, of course, those of the visible exterior elevation. Its variegated, textured brick and rough-hewn limestone contribute to a materially diverse facade, defined by the projecting bays of stacked porches on either side of its front entrance. Soldier brick tops each of the window and porch openings, and their undersides are lined with stone sills. On the third story, sills are replaced with a single, continuous course of stone and brick headers. Gable roofs with flared eaves project out over the third-story porches, seemingly drawing them into the building and minimizing the ‘colonnaded’ aesthetic so common to Kansas City apartment ‘flats’ of the previous decade.

It is in the details that the Cottesbrook is distinguished from any other building, and through which architect Nelle Peters accomplished a masterful communication of the Tudor Revival. The half-timbering, brackets, and bargeboards of the gables most immediately convey this styling, but so do several other features. Between the gables is a shingled parapet pierced with an eyebrow dormer. A pair of chimney clusters, topped with terra-cotta chimney pots, rises above the outward-facing sides of each front-facing gable, while the larger, functional chimney is concealed on the western elevation. The brick parapet lining the rest of the building is decorated with a floral insert, situated as a diamond in a way that creates a crenellated effect, and topped with stone coping. A stone foundation of rough-hewn limestone blocks serves dual purposes, functional and ornamental; stone blocks project several feet above the foundation like quoining, appearing to ‘climb’ up the brick façade’s corners. This placement of limestone, also present in the Vanity Fair building next door, as well as the David Copperfield at 804 West 48th Street, not only accents the corners, but “provides a fanciful element to the facades.”2

The primary entrance is a focal point of ornamentation, recessed behind a cast stone entry portal. Decorative elements on the portal and short brick parapet above include floral elements, a central cartouche, volutes, and a pointed finial. While this kind of ornamentation is undoubtedly associated with expression of the Tudor style, it would not be entirely out of place in the context of Spanish Revival either—facilitating continuity with the nearby Plaza in a way that might otherwise seem unintuitive.

Woman’s Work

The Cottesbrook, along with other apartment buildings along the western edge of the Country Club Plaza, is a notable inclusion among the portfolio of Nelle Peters (1884-1974). Perhaps Kansas City’s most prolific architect, Peters has been attributed with the design of over 1,000 buildings. Active mostly in Kansas City, with other significant projects in Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, her architectural practice extended as far as North Carolina, New Jersey, and Ohio (as well as in other parts of Missouri).

Peters’s prodigious architectural output and the admirable impacts she had on the landscape of Midtown Kansas City are the stuff of legends, and a story that merits its own telling.3 What is sure, however, is that the trailblazing female architect was at the peak of her career in the mid-1920s, when she was fully supporting herself (following a 1923 divorce) as a designer of individual buildings, apartment-hotels, and apartment courts. She designed a total of 41 documented building projects in 1923, more than any other year of her career; this also marked a peak of residential construction in Kansas City.

Peters was involved in the design of all the West Plaza residential buildings in the mid-to-late 1920s. This portion of the West Plaza neighborhood was developed by Charles E. Phillips, a towering character on the Kansas City real estate scene. Phillips’s association with Nelle Peters began in 1913, and he would go on to become “her principal source of employment,” as he eventually “received credit for building more large apartment buildings than any other developer in Kansas City.”4 With the exception of his downtown hotel, Phillips commissioned Peters to design most of his multi-family developments, and her architectural output often ebbed and flowed with the tide of his development activities. The Cottesbrook is just one among the ‘Poet’s Buildings’ (also known as the ‘Literary Block’), comprising all the low-rise apartment buildings along 48th Street. It is most likely named after Cottesbrooke Hall, an English estate believed to inspire Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. The rest of the Literary Block includes the Vanity Fair, the Cottesbrook, the David Copperfield, and three two-story buildings from 4728-34 Summit Street, known as the “Green Gable Apartments” (no longer extant). All erected between 1927 and 1929, these buildings employed a whimsical interpretation of Tudor style. To the west of the Cottesbrook, Peters also designed the ‘Painter’s Buildings’—the Rousseau and Cezanne, respectively—combining Art Deco flair with a Spanish Revival palette. Peters was also tasked with overseeing construction on six nearby projects: the Mark Twain, Eugene Field, Thomas Carlisle, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Robert Browning; by architects Elmer Boillot and Jesse Lauck, who worked out of an office just a few doors away from Peters’s on the tenth floor of the Orear-Leslie Building in Downtown Kansas City.5

A Century Gone By

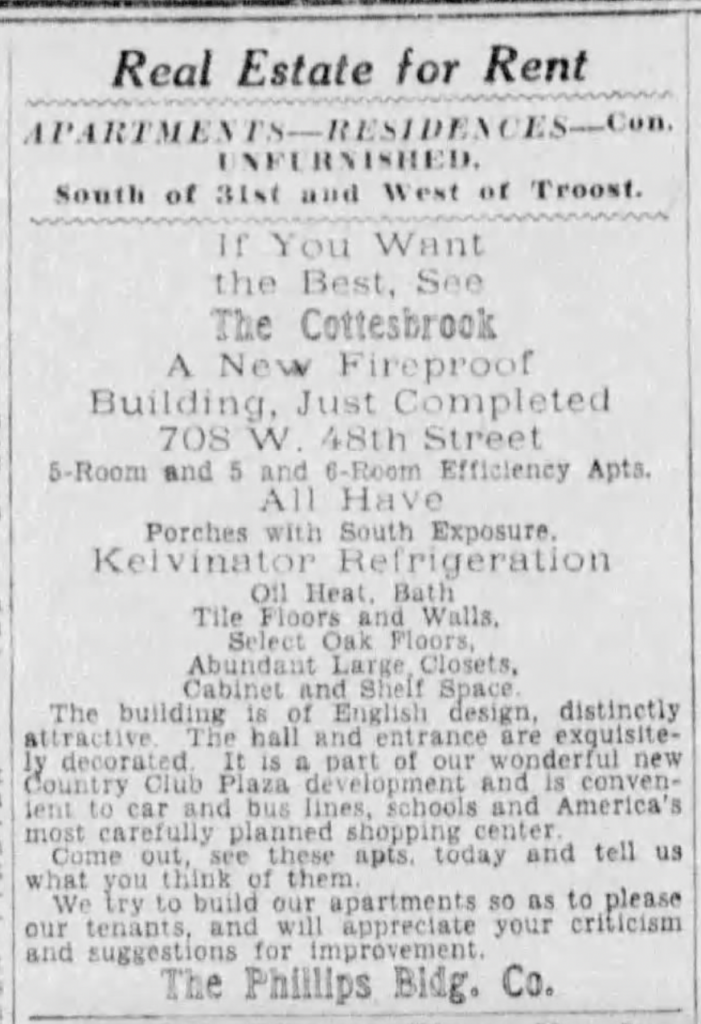

The Cottesbrook debuted in 1927 with an announcement in local papers that, “If You Want / the Best, See / The Cottesbrook,” highlighting its new construction, fireproof materials, and Kelvinator refrigerators. The same advertisement proffered porches with south exposure and touted “Abundant Closet Space,” in addition to more standard features like oak floors, oil heat, and a bath. Notably, the Phillips Company stated its mission of pleasing tenants and welcomed comments for “improvement,” only after proclaiming the superiority of the Cottesbrook and Country Club Plaza’s facilities and access to transit.

Cottesbrook Apartments advertisement, Kansas City Star, Sunday, Sep 25, 1927. Page 36.

A glance at three couples recorded in the 1930 US Census gives a snapshot of the Cottesbrook’s tenant population.6 Some names included Douglas and Dorothy Thomas, Robert and Alma Watkins, and Robert and Frances Hoffman; the men worked as a “Research Engineer” for “Electrical Products,” a “Sales Executive” for the meat-packing industry, and a “Sales Supervisor” for a roofing firm, respectively, and each of their wives held no recorded occupation. The three couples—all white, childless, and seemingly in higher-paid positions—could afford more than the average Midtown rents of the day, paying $67.50, $70, and $82.50 a month, respectively. The difference in pricing might be accounted for by the varied unit sizes; 12 of the 18 units featured six rooms (two-bedroom configuration), while six units had five rooms. The building retains this unit make-up in its present state, with two-bedroom units of 850 square feet each and one-bedroom units around 650 square feet. Many of the units conform to the original kitchenette format, with a narrow kitchen abutting a main room or dining space, but several have seen these walls reconfigured. A common interior motif of the units is the ogee (pointed, but curved) arch, which defines many of the interior divides between rooms. Two basement units were added prior to 1969 and may have initially accommodated a building caretaker; their remnants were dismantled in 2015 and incorporated into a storage area for tenants.

The building retains many of its character-defining features with few other changes. The foyer features a hodgepodge mosaic floor, with randomly distributed marble pieces of different sizes and colors, and a series of lacquered prints of works by William Shayer (a Victorian-Era British painter) hang above the mailboxes. There is a short staircase between this entryway and the first floor hallway. Each hallway is carpeted, featuring dental molding and walls of plaster with a textured finish.

Some of the most visible exterior changes occurred in the last few decades; records still attest slate shingles as the roofing material as recently as the late 1980s. Documenting the Cottesbrook’s original condition means returning to a 1940 tax assessment photograph, where the original multi-colored slate is visible on the gables, as well as finials rising above the ‘gingerbread’ embellishment on the gable front. Finials also adorned the now-demolished low-rise constructions of Nelle Peters on Summit Street (4728, 4730, and 4734 Summit Street), and they remain intact on the Pennbrooke Apartments of the Quality Hill neighborhood—another Tudor Revival complex designed by Peters. It can be assumed that the Cottesbrook’s loss of original slate roofing and removal of its finials occurred contemporaneously. A 2014 renovation resulted in removal of the building’s storm windows and re-opening of its porches. Stucco hip walls–added sometime after 1940–were removed from the third-floor porches and wrought-iron balustrades were introduced.

Although some losses and replacements have displaced some of the original exterior elements, the building retains its ability to communicate its design influences and historic character. It generally retains integrity of design and materials to the appearance and makeup of its period of significance, and it remains an excellent example of both its property type and of the Tudor Revival style. Today Peters’s legacy is promoted through local and national historic designations of properties she constructed throughout Kansas City. The Nelle E. Peters Thematic Historic District protects the exterior integrity of the Cottesbrook Apartments, as well as the Vanity Fair, Rousseau, Cezanne, David Copperfield, and the Washington Irving Buildings (as well as other, non-contiguous Peters designs elsewhere). This recognition received reciprocal recognition by the National Park Service as well, achieving status as a Certified Local District (enabling recognition and benefits commensurate with National Register listing). A 2015 attempt to amend the local district and its protective measures encompass the Green Gables Apartments—the set of two-story buildings that Peters and the Phillips Company constructed in similar style just a block away—was unsuccessful, and the three buildings were demolished soon after.

“Out of respect for Nelle Peters and the history of the building,” says Shane Glazer, owner of the Cottesbrook since 2022, “the building deserves to be called what it was originally named.” Glazer added that “Ever since (even before) I purchased the building, using the wrong name didn’t feel right to me. I am sorry that it took me three years to change the name back, I certainly feel better about it now, and I’m happy that I finally did it. If Nelle were here she’d be happy as well.”

- Sally Schwenk. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form. “Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City, Missouri.” Sally Schwenk Associates, Inc., 2007. Section F, Pgs. 13-15. ↩︎

- Becky Cotton Zahner, “Nelle E. Peters Thematic Group.” Kansas City Register of Historic Places Register Form. 1989. Pg. 7. ↩︎

- Unfortunately, there is no book-length treatment of Nelle Peters’ life and career for interested leaders, but a 1988 article in the State Historical Society’s Missouri Historical Review, by George Ehrlich and Sherry Piland, provides the best available overview. A virtual career summary can be found via Pioneering Women of Architecture’s well-illustrated profile. ↩︎

- George Ehrlich and Sherry Piland. “The Architectural Career of Nelle Peters.” Missouri Historical Review, Volume 083 Issue 2. January, 1989. Pg. 166. ↩︎

- Tom Taylor, “They Built Kansas City: Elmer Boillet and Jesse Lauck.” Lecture delivered July 10th, 2016. ↩︎

- 1930 Census Records, accessed via Ancestry.com. ↩︎

What a great article! I live next door to this building and noticed the name change and wondered what was up with that. Beautiful building … really jealous of their great porches!

The Summit St. apartments you referenced, I’m told were a nightmare when it rained. The empty lot where two of them stood are swamps in the rain.

Would love to see an article like this about Rousseau and Cezanne.