In Part 1 of this post, we met the athletic and successful Morley family. Father P.J. Morley built a number of houses in Midtown. His son, Washington Irving Morley, became a popular architect, designing 15 homes in the Valentine neighborhood. But things would turn bad for Irv Morley.

What went wrong, according to Morley’s own account, was “I let wine and women get to me.”

One of the Valentine homes designed by Irv Morley, at 3721 Pennsylvania.

In 1910, Morley was riding high. He was working steadily as a Midtown architect. He even ran, unsuccessfully, for alderman that year. But then, he recalled, he started spending time in cabarets, and said his troubles began at the Jefferson Hotel, an infamous location at 6th and Jefferson owned by Tom Pendergast.

The ill effects of cabarets at the time were a subject of robust debate to some in Kansas City. The new and popular entertainment venues featured, most often, young women singing for an audience. In one Kansas City Star article, a reporter described a show at 12thand Main that consisted of young women wearing pink and handing out roses to the patrons and singing. The audience, according to the reporter, consisted of some men accompanied by their wives.[1]It seemed harmless enough.

But there were also stories of “wicked” shows in Paris, New York, St. Louis, and even Kansas City. In fact, in April of 1913, St. Louis cracked down on cabaret performances, with the police chief defining what would be legal this way. “Women may sing in cafes and hotels providing their exhibition is not depraving to the public. Just what is depraving depends on the circumstances.

” The chief said he believed “such songs as ‘Hitchey Koo,’ ‘When I Get You Alone Tonight,’ and ‘All Night Long’ rendered by women in loose resorts may be considered depraved. They should not be allowed, he says. But the warbling of arias from ‘La Boheme’ and ‘Aida’ and selections of similar ilk in the dining rooms” will be in perfectly good form.”[2]

The police chief of Kansas City liked the idea and copied it here. In July, the policy was replicated here.

The new police ruling went into effect last night. There will be no more dreamy waltz songs in shrill soprano, no more silky gliding syncopation oozing from downtown cafes after 11:30 p.m. The music must stop half an hour before midnight and the new day must be ushered in without melody or rhythm.

“Cabarets Under New Order, “Kansas City Star, July 20, 1913, page 1.

And that isn’t all. Before the appointed hour the cabaret singers must confine themselves to certain limits. They must stand up by the piano. Mustn’t get down on the floor and tango up and down between the tables among the late diners.

Furthermore, the audience is hereafter enjoined from joining in on the chorus. Those inspired with the swing of cabaret songs must step outside if they wish to assist in the performance. The singing in the café must be done by those who are paid to do it.”[3]

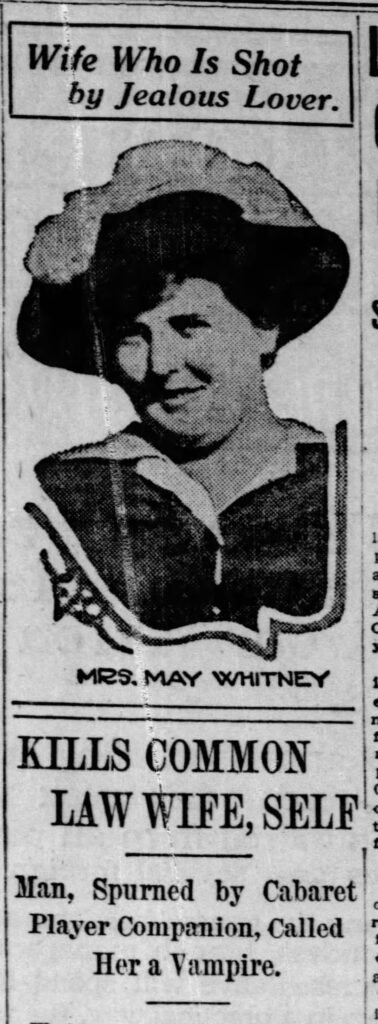

The singer who, according to Irv Morley, led to his downfall was named May Whitney (aka May McKnight). She had performed in Kansas City at the Hiawatha Café at 11th and Baltimore and the nearby Baltimore Hotel. Although she was a piano player and cabaret performer when they met, May appeared to give that up after she met Irv Morley. Instead, they spent time together watching the shows as audience members.

The something went wrong between them. They went to Chicago together, perhaps to begin a new life away from the vices of the cabarets. But May became upset after Irv passed some bad checks and she left him. Soon she was entertaining again at Spangenberg’s café, a place they had frequented together. Morley went to the cafe to plead with May. What happened next became front page headlines across the country.

“When the curtain rang down on the cabaret performance in Spangenberger’s café, in Clark street, near Chicago avenue this afternoon, it rang down also upon the stormy love affair of Washington Irving Morley of Kansas City and Miss May Whitney, once of Boston, later of Kansas City, and still later of Chicago.

“A dozen people lingering in the café heard two pistol shots. They saw May Whitney, one of the performers, sink to the stage. Morley fell beside her.

“The man was dead when they reached him. The woman was dying. The two, who had lived together for five years, presently lay side by side in the same morgue.”[4]

At the end of his life, Morley called May a vampire, and a friend of Irv’s called her a deceiving woman in looks, with a Madonna-like face which gave the impression she could not do anything wrong.

Morley left a suicide note offering his advice.

Young men, forget the good time stuff,” he wrote. “Remember, do not get infatuated with a woman of doubtful character. They can never lead to any good.”

“… I’ve had my fling, and have ridden in taxicabs and limousines, etc. but now a trolley car won’t even stop for me. But I am going to the Great Beyond, and I’m going to take the creature with me that has caused me more bad luck, heartaches and everything else.

“I cannot live with her and I cannot live without her. If the world will only forgive me. Goodbye all. W.I. Morley.” [5]

Postscript: More Tragedy for the Morley Family

One more tragedy struck the Morley family a decade later. Washington Irving Morley’s brother James was shot on the lawn of a home at 5817 Charlotte. James had gone to visit his 20-month-old daughter. His estranged wife, apparently fearing he intended to kidnap their child, pulled a revolver from her purse and shot him three times. As he staggered out of the house into the yard, a large crowd of neighbors who had been sitting on their porches gathered.

Mrs. Morley followed James, wailing, “Oh, honey, did I hurt you?”

She was informed of his death a few days later at the sanitarium where she had been taken. At the funeral, the priest, Father O’Maley, characterized the tragedy as an inexplicable case resulting from the heat of passion. “It may be said truthfully that the one who loved most took the life of the other, for she loved him dearly. Her heart is in the casket with him now and she gladly would change places with him. That is not remorse. It is love.”

[1] “In an Expurgated Bohemia: An Hour with the Kansas City Cabaret Show,” Kansas City Star, Oct. 20, 1912, page 44.

[2] “In the St. Louis Cabarets,” Kansas City Star, April 24, 1913, page 1.

[3] “Cabarets Under New Order, “Kansas City Star, July 20, 1913, page 1.

[4] Kansas City Journal, Sept. 28, 1915, dateline Chicago.

[5] “Irv” Morley’s Warning,” Sept. 29, 1915, Kansas City Times.