Anyone who has combed through reams of Jackson County property records knows that many of Kansas City’s early subdivisions bear the family name of prior owners–often those who, before the advent of development pressures from an expanding city center, had occupied the land themselves. One can all too easily assume, looking in the rearview from today’s professionalized real estate industry, that the people who platted Midtown neighborhoods and sold off lots to residential or commercial users were exclusively a cohort of men—property speculators, realtors, and builders. That paradigm is disproven, however, by the record of truly diverse citizen-entrepreneurs who played a role in shaping the expansion of Kansas City’s urban footprint.

Mrs. Mary T. Whiteside exemplifies the type of early Midtown resident who both lived on and profited from previously accumulated tracts of land, selling off sections throughout the years as subdivisions proliferated into the heart of today’s Volker neighborhood. What follows is a short account of her life based on publicly available records and contemporary newspaper reports.

Born in Delaware, Ohio in 1848 as Mary Thompson, the fourth of five children in a household that also included three boarders, young Mary’s family relocated to Wabash, Indiana sometime after 1860. It was there she met and married her husband William H. Whiteside, who is recorded working as a banker in the 1870 census. Mary’s occupation was listed as “Keeping House.” The couple had two children, daughter Edith and son Madison, before moving to Kansas City in 1879; William began work as a real estate agent the following year.1 At the time, the family was living downtown along Walnut Street, adjacent to today’s River Market complex. Mr. Whiteside, evidently best characterized by a summary of his business endeavors, was described in his wife’s obituary as rising to the position of partner in the firm of “S.F. Scott & Co., which handles large tracts of land on which are now situated much of Kansas City’s business district.” The same article states that he died at the family home on 39th Street around 1904.2

“[S]he had devoted her attention principally to looking after her substantial property interests here.”

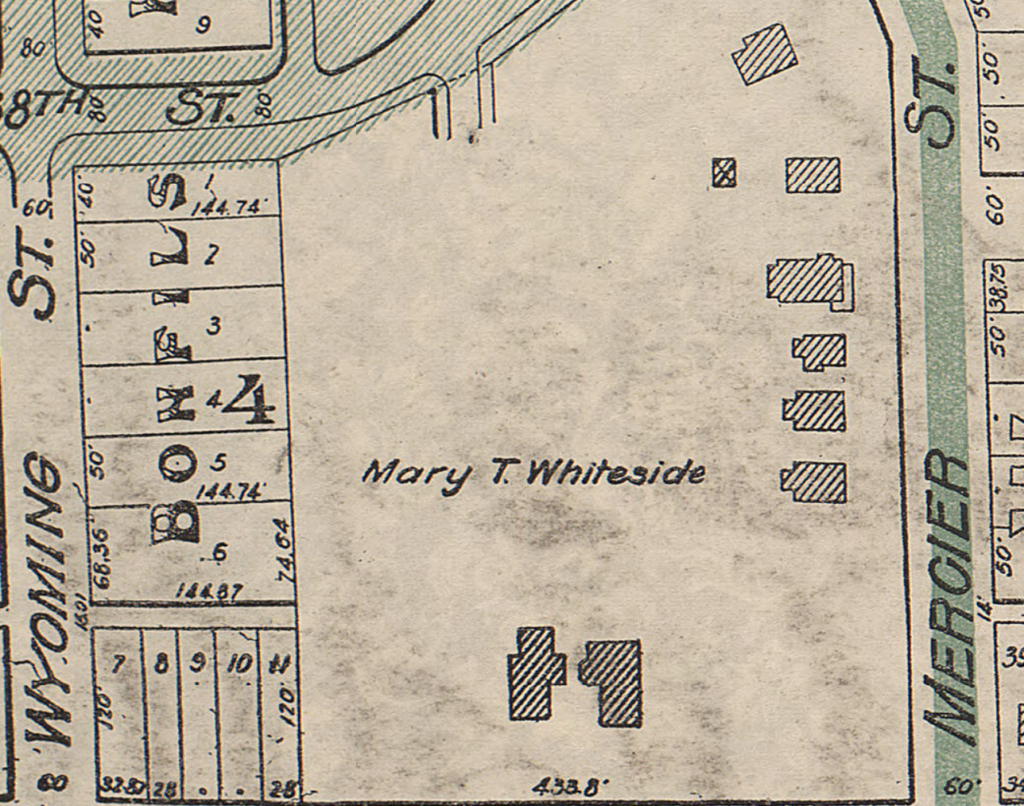

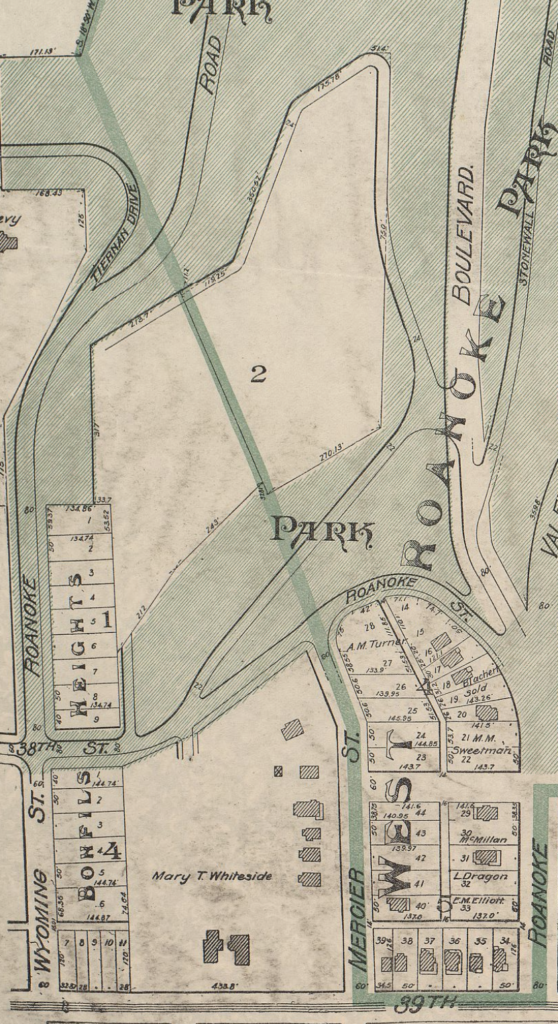

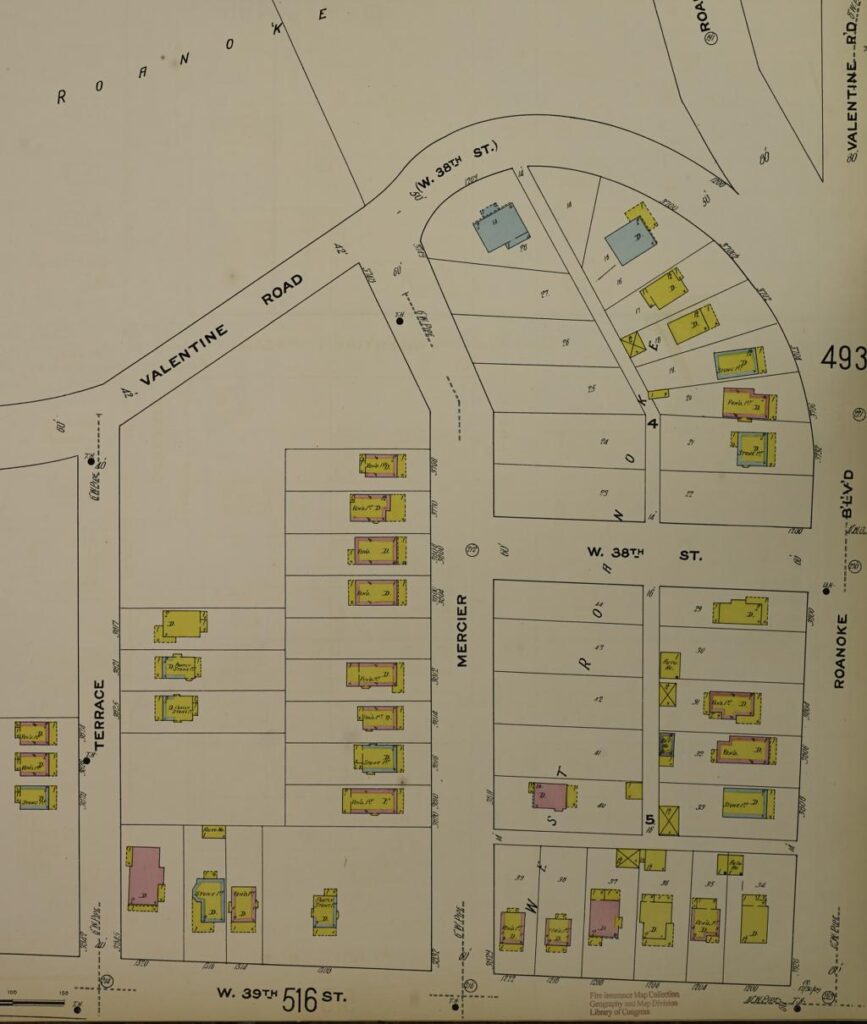

In the 1900 census, Mary T. Whiteside is listed as living alone as a divorcee on the southernmost area of her property holdings. At 54 years of age, she is named as the owner (with a mortgage) of a property numbered 1320 Mercier Street, with her occupation labeled simply as “Capitalist.” Later city directories (1912, 1913, and 1914) show her occupying the same block, though the numbering for her dwelling place changes to 1320 W 39th St. by the latter of these records. A 1907 map of the Roanoke residential district of Kansas City, from the South Highlands Land and Improvement Company, inscribes “Mary T. Whiteside” in the middle of the city block ringed by Wyoming St. on the west, 38th St. (later Valentine Rd.) on the north, Mercier St. to the east, and 39th St. to the south. Two houses are shown facing 39th St., as well as six houses facing Mercier St. The western edge of the block is divided into a line of platted lots (which continues onto the block to the north) with the name “Sorpils Heights.” The presence of a gate is indicated on the north side of the block, which opened inward from 38th St. and was approximate to the location of today’s northern outlet of Terrace St. onto Valentine Rd.

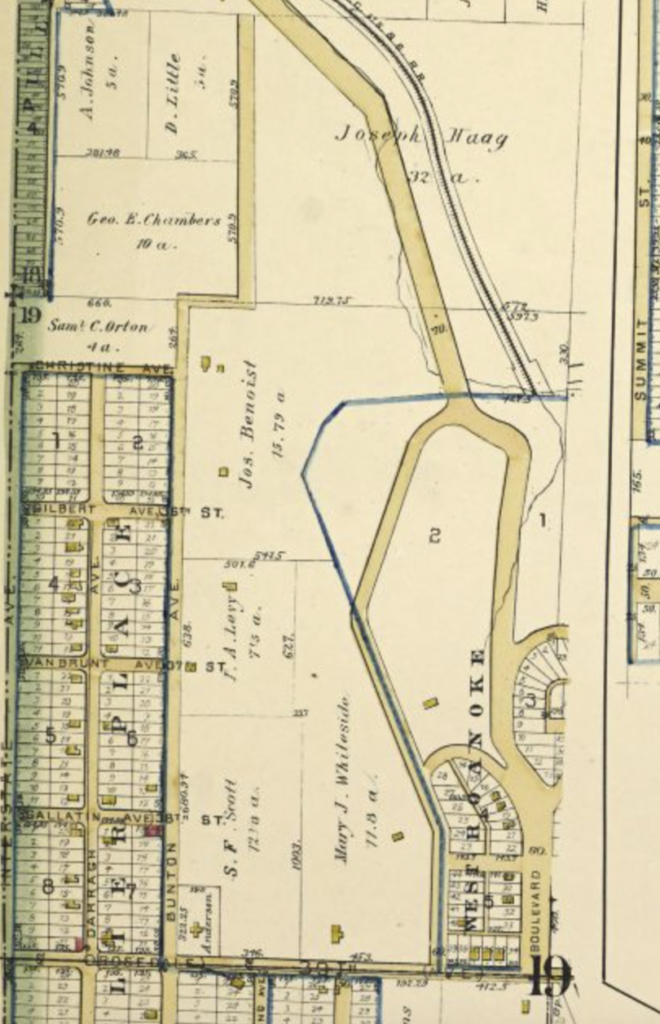

It can be difficult to visualize property ownership during this period, as records are often scarce, and there were no Sanborn maps for the Town of Westport prior to its 1897 annexation. A city-wide plat map from 1891, however, provides some valuable insight into property ownership in the southern hinterlands of Kansas City. The 1891 map inscribes “Mary J. Whiteside” within a strip of land approximately 1000 feet from north-south at its longest point and 300 feet west-east spanning from today’s 39th St. to West Roanoke Parkway and Karnes Boulevard. A frame house is shown standing on the far southwest corner of the property, and a frame outbuilding sits adjacent to today’s intersection of Mercier and 38th Street.

When it came time to sell off some of the family’s land, Mary signaled her eagerness for a conversion of real property to cash value by petitioning the city to create new parcels on the southeastern corner of her holdings. According to the Kansas City Journal, she personally addressed the Westport City Council for ten minutes during a meeting in November, 1897.3 Council delayed the matter to be reported at the next week’s meeting, which was one of their last times convening as a body; the special election for annexation (joining Westport with Kansas City) was held on December 2nd, and the City Council subsequently disbanded. Mary further demonstrated her acumen as a diplomatic developer by donating a sewer right-of-way to Kansas City in 1903, alleviating an “urgent” and “vexing” problem for which she was publicly credited in contemporary news accounts.4 The sewer’s anticipated construction costs, accordingly, plummeted from an alternative price of $45,000 to roughly half that amount. One assumes that installation of sewer infrastructure might also have increased her land’s value by increasing capacity for adjacent development.

The earliest newspaper report of land deeded from Mary Whiteside to another party appears in 1905; neither the plat nor the other transactor are named.5 In 1911, Whiteside donated a substantial portion of her landholdings to the newly created Roanoke Park; this included the western extremity of today’s park in the vicinity of the tennis courts, as well a spit of land along the westernmost terminus of today’s Karnes Boulevard where it feeds into Wyoming. In this tactic, our protagonist was preceded by another private landowner, H.T. Abernathy, in 1909 and by the The South Highland Land and Improvement Company, who donated the largest tracts in 1901 and 1905. In doing so, Whiteside established herself as a central actor in the distinctive origination of Roanoke Park, a public green space created by a series of seven donations of land. Most of these parcels consisted of rugged terrain and were not seen as suitable for ‘quality’ development; private landowners, accordingly, saw donation as the best means of increasing the value of their surrounding properties. The 1913 Van Horn School at 3715 Wyoming St., renamed after William Volker 1948 and, later, for Gordon Parks, was erected mostly on land formerly owned by Whiteside, though it is unclear when this transfer took place.

According to city deed records, Whiteside created two new subdivisions out of her landholdings in 1908, with eight west-facing parcels on the east side of Terrace St. labeled as “Whiteside Place” and twelve parcels on the west side of Terrace St. as “Whiteside Place No. 2.” The latter comprised two north-facing parcels, A and B, along Valentine Road and C through L facing Terrace St. 1909 Sanborn maps show houses already standing in each of these newly created subdivisions. In 1912, Whiteside platted the northern section of the block encircled by Valentine Road, Mercier St., Terrace St., and 39th St. into six parcels, referred to as “Whiteside No. 3.” These three subdivisions still bear her name to this day.

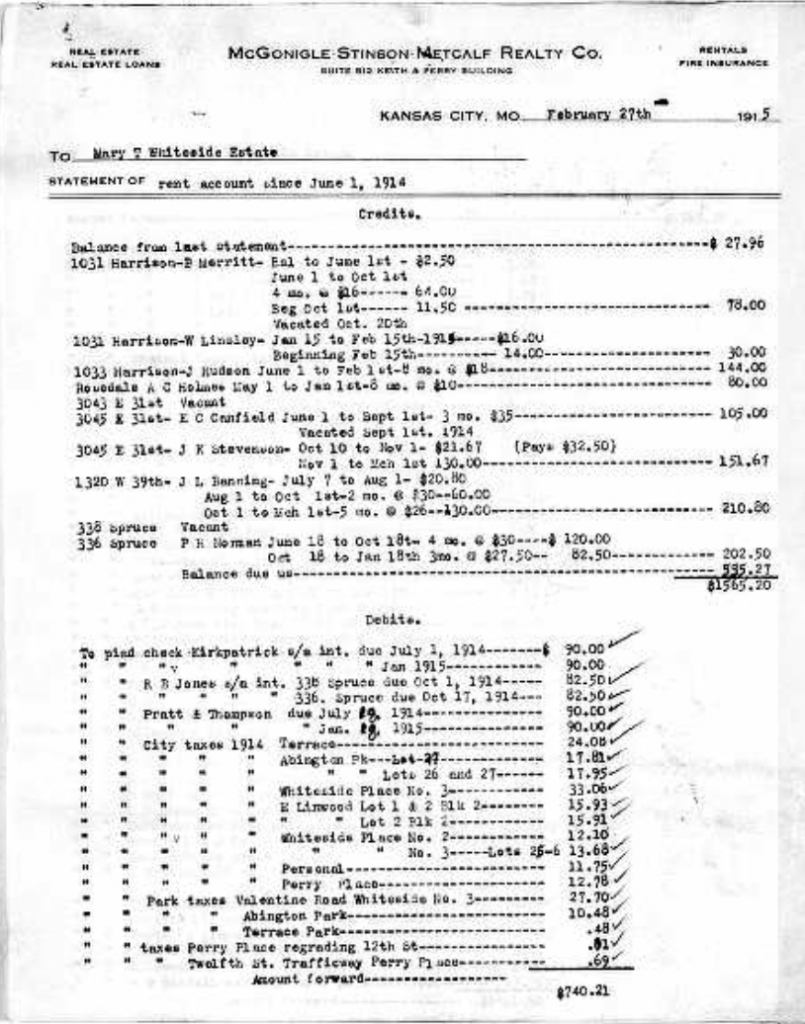

The 1908 City Directory’s real estate section includes an entry indicating she maintained an office at 1410 W 39th Street (a commercial building that remains standing today), located just west of her personal home. This might be understood as proof that Whiteside personally conducted transactions and oversaw her portfolio of real estate investments. Illustrative of the kind of returns our heroine investor reaped from small-scale land sales was a pair of lots she sold in 1912 to H.C. Pouder, founder of the Pouder-Pomeroy Oil Company, for a combined $9,600; this included the southwestern corner of the intersection of Valentine Rd. and Terrace Street. In that same year, Whiteside wrote her last will, bequeathing all her real and personal property to her son, Madison, and daughter, Edith. Following her death in 1914, probate records attest to the extent of her ongoing business endeavors; rental income was streaming in from over half a dozen properties distributed across the city. These records indicate rent collection from multiple families connected to seemingly single-family residences on the East Side. Other assets included a barber shop in Rosedale on the Kansas side and a collection of mortgage notes which appear to be owner-financed property sales (again, expanding well beyond Midtown). Architectural survey records from the Whiteside tracts in Volker record only a single house, 3817 Terrace, built in 1907, as having been built by the “Whiteside Realty Company.” This may represent an undercount of Whiteside’s development activities or simply present a reflection of her tendency to sell lots on which other builders would erect homes.

An Incomplete Story

Census records and newspaper mentions can only go so far in painting a picture of a person’s life. Sometimes, they can seem at odds with one another. While listed as living alone and having been divorced in the 1900 census, Mary’s obituary states that, just a few years later in 1904, her husband William died at their family home on 39th Street. Children Edith Sheridan and Madison Whiteside had moved away years previously, the latter to Columbus, Ohio to be a dynamite salesman and, for Edith, a life in Chicago, where she raised a daughter alone following the death of her husband. Edith, an interior decorator of “rare artistic skill,” apparently hosted her mother throughout much of the last chapter of her life. It was in Chicago that Mary petitioned to divorce William, telling a judge that her husband declared one day in 1890 “that business was bad and he was going elsewhere.” “Not a word has his family heard from him,” Mary and Edith attested in 1896, though he was said to be residing in Excelsior Springs. The decree was granted on the basis of desertion. The story of his death leaves us to speculate that a reconciliation occurred thereafter.

The family had attended Grace Episcopal Church, with Mary’s obituary citing her active membership and, “earlier in her life,” being “conspicuously identified with welfare movements incidental to her church connection.” Edith’s wedding there was written up (preemptively, even) in the Kansas City Star as the “event of the week in society,” suggesting a certain social standing for families of both parties, entailing a limited guest list, unostentatious ceremony, and “lavishly embellished” bouquet. No other information is readily available regarding the family’s other social engagements or Mary Whiteside’s funeral rites in 1914.

Among the more mysterious aspects of the Whiteside family’s paper trail is the question of to what extent, exactly, they lived in the family home at 1320 W 39th Street. In the 1900 census, the home is said to be the dwelling place of the Wilson family: John (a cattle salesman), Mary, and their five children. The census-taker’s entry for Mary Whiteside is separate, though adjacent, and lists the street and number “Mercier / N.W. of 38th ave,” suggesting that Mary might have established herself on some other part of the yet-to-be-subdivided plot. A 1907 city directory lists the now-widowed Whiteside as living at “38th sw cor Mercier,” which is difficult to square with the previous census absent another move around the property or a mistake. During the intervening years, the house at 1320 W 39th had been advertised for lease in local newspapers, first as “9-R MOD., YARD; $35.” in October 1903, then once more in November 1905, billed as “8-room mod. Brick; only $25.” It seems she had again inhabited the home prior to her death in May 1914, though it was advertised for rent shortly after, and the probate records show J.L. Banning having taken up residence. A box-maker by trade, Banning, wife Rose, and family would remain through at least 1920.6

Reviewing maps of the property as it changed over time, one can only imagine that Mary Whiteside, in the absence of her husband and children, moved into one or more houses on Mercier, either the lone frame structure shown already standing in that vicinity in 1891 or one of the frame-built, brick or stone facade (mostly shirtwaist) homes built in subsequent years. Sometime between 1925 and 1940, the substantial brick house on what became the corner of 39th and Terrace came down. A commercial building was later constructed on the site in 1957. Surprisingly, nearly every other home built on the block during Mary Whiteside’s lifespan remains intact today, including two homes (one with stone facade at 1318 W 39th, one with brick at 1316 W 39th) just adjacent to the original Whiteside home place.

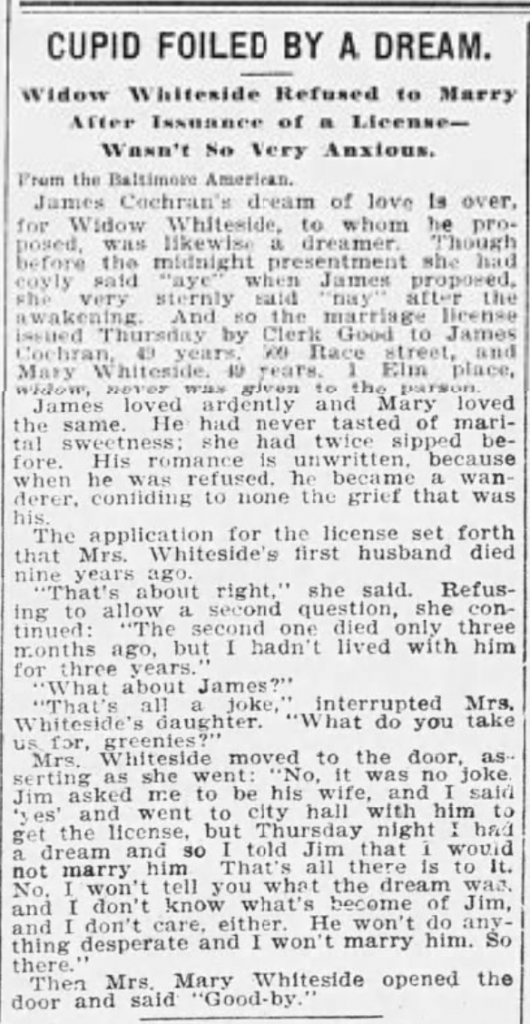

Postscript: This kind of historical research abounds in dead ends and extraneous stories, some of which can be just as fascinating as the primary subjects. A 1901 syndicated article appearing twice in Kansas City newspapers, though taken from the Baltimore American, featured a woman named Mary Whiteside as the subject of a brief human interest story describing her rebuffing of a suitor by the name of James Cochran. Entitled “Cupid Foiled by a Dream,” the article tells of how a 49-year-old widow’s dream prompted a last-minute exit from a marriage for which a license was already issued. The humorous article is found among the images below, though be aware that it applies to a Ms. Mary Ida Whiteside, not the Mary T. Whiteside we have come to know!

- US Census record, William Whiteside, 1880. Accessed via Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- “Mrs. Mary T. Whiteside Dead,” The Kansas City Times, Thursday, May 28, 1914. Pg. 2A. ↩︎

- “Winding Up Business, ” Kansas City Journal. November 9, 1897. Pg. 3. ↩︎

- “Gave Right-of-Way for Sewer,” The Kansas City Times. April 9, 1903. Pg. 2. ↩︎

- The Kansas City Times, November 23, 1905. Pg. 7. ↩︎

- US Census Records, J.L Banning, 1920. Accessed via Ancestry.com. ↩︎

Excellent profile Ethan! Great job.

In my much less exhaustive research I came across her 1899 proposal to route what would become Valentine Road across her land, with the motivation of self-enrichment plainly stated:

—

WOMAN WITH LEVEL HEAD

She Believes Boulevards Increase the Value of Her Property and Will Give Free Right of Way.

Mrs. Mary Whitesides, who owns a large tract of unplatted land west of Roanoke place, was before the park board

yesterday with a proposition to make a slight change in the Thirty-fifth street boulevard, so as to run it through her grounds. Mrs. Whitesides said she intended to plat the ground immediately and asked that the boulevard go on Thirty-fifth street to Broadway, south on Broadway to Thirty-sixth street and then west through her property. As a consideration she offered to give free of charge whatever land was needed for the boulevard where it passed through her property, and further to deed to the city a tract of land for park purposes. Her offer was taken under consideration by the board.

—

– The Kansas City Journal, January 5, 1899