Some blocks of Midtown Kansas City offer more insights into history than others. That is true of the block from 50th to 51st between Main and Walnut Streets. Two weeks ago, we offered the story of one house where prohibition agents discovered “one of the finest equipped distilleries ever found in Kansas City.” This week, more about the block’s original owners and the prolonged fight over commercial encroachment as the area south of Brush Creek developed in the 1920s and 1930s.

As part of our Uncovering History Project, the Midtown KC Post is looking at each block in Midtown, including a set of 1940 tax assessment photos available for many blocks. (Many people seem confused by the tax assessment photos, including a man holding a sign. Here’s the story behind them). This week, the second post on the block from 50th to 51st Terrace between Main and Walnut. Last week, the story of one house where prohibition agents found “one of the finest equipped distilleries ever found in Kansas City.”

McDonald Family Once Owned the Block

John McDonald was a paint manufacturer and civic leader. He had served as presiding judge of the county court and city council member. His nine children grew up in the large family home on the southwest corner of 51st and Main, in a largely-undeveloped area.

After John McDonald died, the Glencoe Company platted the original farm into the Glencoe subdivision of residential lots and commercial properties. McDonald home was razed and stone taken from the hill for buildings in the area when the land was leveled

One of McDonald’s sons, Monsignor Thomas McDonald, founded Visitation Church in 1909 and served there until his retirement in 1957. He formed a parish and held its first service in his parents’ home. The current Visitation church at 5154 Main, opened in 1916, was built on land donated by the McDonald family.

Another son, Sidney James McDonald, died while eating at a restaurant at 5103 Main in 1938, after the family farm had been subdivided.

The shops at 51st and Main were mostly built in the early 1930s. Early occupants included Great A&P Tea Company, E. Murray Ellsworth’s flower shop, and the Betty Jane Ice Cream Parlor. Cliff and Ola Stouffer operated the County Club Café there from the late 1930s until the early 1970s. The shops also housed a supermarket, a dry cleaner, and other businesses serving the neighborhood.

Well-Know Residents Move Into New Homes

After the McDonalds sold the property that makes up the block, the commercial corner was erected at 51st and Main, and homes filled in the rest of the block. Close to streetcars, churches, schools and stores, families moved in beginning in the early 1920s.

Many of the early residents were prominent business and civic leaders. Dr. LeClair Lambert, president of Mercantile Home Bank and Trust, lived at 5100 Walnut from the mid 1930s through the end of the 1940s. The George Nicholl family lived at 5140 Walnut at least from 1929 through 1937. Mr. Nicholl was secretary-treasurer of Lacey-Nicholl Wholesale Florists and part owner and manager of Furniture Fair furniture business.

In 1934, the house at 5131 Main became briefly famous on WHB radio, when it became the “Cook’s Half and Half House.” Half of each room was redecorated with paint, while the other half of the room was unchanged.

In 1922, Frank Sebree, senior member of the law firm Sebree & Sebree, bought the home at 5119 Main from Glencoe Realty. The house was formerly owned by Judge Arba S. Van Valkenburgh.

Tensions Rise Over Commercial Encroachment into Residential Area

As early as the late 1920s, this area of Kansas City was strained by the need for commercial space to serve the growing population of Kansas City. By 1926, residents of the block also were fighting against the development of multi-family properties. W.C. Harrington told the board of zoning appeals in 1929 he opposed a two-story apartment building proposed for 5126-36 Main to house twenty families.

“There are acres of vacant land north of Fifty-first street zoned for apartments,” Harrington said at a city hearing. “Ours is a home district. Virtually all of us own our homes. Each house has a range in its kitchen and a cook to prepare its food. We are not cliff dwellers. We built our homes to live in, not to park in. We object to encroachment of flats and are here seeking protection.”

That proposal failed.

In 1930, residents joined a fight against a proposed gas station on the block, part of a larger concern across the city that pitted oil companies against home owners. A few years later, residents were telling the city that business zoning to the north had made their properties useless for residential purposes. During several debates at city hall, residents argued that the situation on the block showed the need for a clear zoning plan that protected residential areas from business encroachment.

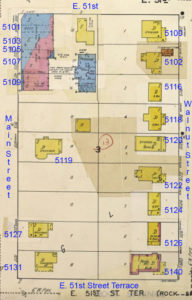

The slideshow below shows the remaining homes and businesses on the block as they looked in 1940.

Historic photos courtesy Kansas City Public Library/Missouri Valley Special Collections.