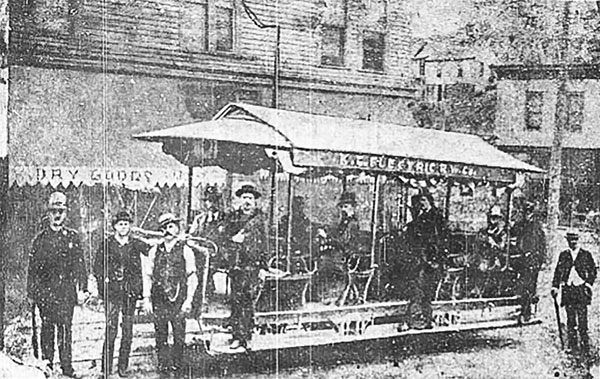

John C. Henry, second from the left, is credited for testing the first electric trolley car along Broadway Boulevard in 1884. Henry is seen in this photo, published in the Kansas City Times in 1954, along with the operator of the car, Charles F. Cobleigh, standing on the running board near the front end of the car.

Midtown played a major role in transportation history, when tests for the first overhead electric railway car took place at Broadway and 39th street in the early 1880s. Inventor John C. Henry gets credit for first using the name “troller” to describe his invention (his workers called the device a trolley, the name that stuck). And some have speculated that, had Kansas City capitalists understood the significance of the Midtown experiment, Henry might have stayed in town and gone even further with development of his trolley, rather than leaving Kansas City and finding backers on the east and west coasts.

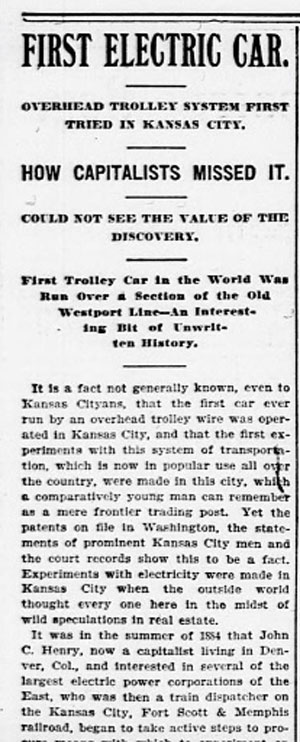

“It is a fact not generally known, even to Kansas Cityans, that the first car ever run by an overhead trolley wire was operated in Kansas City, and that the first experiments in this system of transportation, which is now in popular use all over the country, were made in this city,” the Kansas City Journal reported in 1897. The paper blamed this, in part, on the wild real estate speculation that was going on in Kansas City at the time, perhaps distracting local investors from seeing the value of the work Henry was doing.

In his obituary, the Chicago Tribune called Henry the inventor of the overhead trolley. “It was in Kansas City, in 1883, that he built the first overhead electric road. All previous efforts had been directed to the construction of underground roads, which have not proved successful. Among his improvements were methods for stringing wires around curves and managing the trolley by means of rope.”

The fact that Henry passed through Kansas City at all can be attributed to a plague of grasshoppers.

The Canadian native immigrated to Trego, Kansas in the 1870s and got rich, bought cattle, and became the local postmaster. He also worked as a telegraph operator and became fascinated by electricity.

“He soon thought out a theory for propelling street cars by electricity transmitted by overhead trolley wires. His theory seemed so plausible to himself that he went to a draughtsman living in Wakeeney by the name of Cobleigh, whose son is now an employe in the electrical department of the Metropolitan Street Railway Company at the Twelfth and Charlotte street car shops,” the paper reported.

But just as Henry was getting ready to send his ideas to the patent office in Washington, Western Kansas was hit by a grasshopper plague. He lost his cattle and stores and fortune.

Which is how Henry showed up in Kansas City in 1880 with “but a few dollars in his pocket,” and took a job as a train dispatcher.

He kept working on his idea, and in 1884, Henry organized the “Henry Electric Railway Company” to control his patents and promote “electric locomotion.”

“Walton H. Holmes, then president of the Westport and Kansas City Street Railway Company, whose father built the first street railway west of the Mississippi River, contributed an old mule car and half a mile of track on the old Westport line on South Broadway for the experiments to be conducted by Henry,” the Journal tells us. “A frame building in Westport, near Thirty-ninth street and Broadway, was selected as a suitable powerhouse.”

The paper was critical, however, of his Kansas City backers, saying they were doubtful from the start and frowned on “anything that looked like extravagance in the preparations for the test.” That meant Henry had to find the cheapest materials available, like the rickety old mule car that had seen better days. And, the article pointed out, Henry’s backers didn’t even have enough confidence in his invention to join him for the first ride.

The paper was critical, however, of his Kansas City backers, saying they were doubtful from the start and frowned on “anything that looked like extravagance in the preparations for the test.” That meant Henry had to find the cheapest materials available, like the rickety old mule car that had seen better days. And, the article pointed out, Henry’s backers didn’t even have enough confidence in his invention to join him for the first ride.

“The car was a summer car with two seats running its length, back to back, in the center so the passengers would face outward. However, there were no passengers excepting Henry, who acted as motorman on the car on this trip. After making sure all the machinery was fitted according to the ideas he had so long been studying, Henry took his place on the front platform and turned on the current. The car wheels whirred around. The sparks flew and there was a buzzing sound. Then the car moved. Henry turned on more current and soon he had demonstrated his theory. The car was soon going faster than it had ever gone before. There was a small crowd of people along the line to see Henry ‘make a fool of himself.” They were not gratified and yet they were. The car acquired a speed of about twelve miles an hour when it jumped the track and ran up high on a bank, coming to a sudden halt.”

It took several weeks to make repairs, but tests on the Midtown route continued. Walton H. Holmes remembered his first ride on the car. Just over the small hill south of the Allen McGee homestead (just south of the Uptown Theater today), the car ‘got ahead of the motor.”

“I felt like there were a thousand needles pricking my legs,” Holmes told the Kansas City Times. “Henry saw that the machinery was being knocked to pieces. He touched the motorman on the should, and in his cool, characteristic way casually remarked, ‘You had better put the brakes on, hadn’t you?'”

Henry continued his experiments on a spur of track owned by the Kansas City, Fort Scott & Memphis railroad which ran from the old Union Station to the old interstate fairgrounds near Linwood Boulevard and Broadway.

“He invited Kansas Citians to ride, and some did,” the Kansas City Times wrote in 1954. “One story concerning passengers involved two well-known citizens of the time, Thomas Corrigan, who was interested in horse cars, and Robert Gillham, civil engineer. The car also jumped a track, came to an abrupt halt, and threw the passengers over a hedge unscathed. Gillham, provoked, announced that ‘electric power is not dependable. It isn’t practical.’ Corrigan, picking up his hat, retorted, ‘That’s power enough for me.’”

Despite what Henry saw as success, his backers became districted by the real estate market, and pulled out of his experiments. In the spring of 1887, Henry set up an electric car line with four summer cars and ran it successful until cold winter came and the passengers tired of the novelty. His company went into the hands of a receiver.

Henry moved on to California where he continued to perfect his ideas. He later became the chief expert for the General Electric Company in New York, according to his obituary in 1901 in the Chicago Tribune.

“We are now buying our electric cars from the East when we could have been making them here and shipping them East,” Walton Holmes said later. “But we had out chance and did not have foresight enough to grasp the opportunity.”

Excellent history lesson for any Kansas City Citizen, especially if one’s from the Westport area, like me.

I agree Frank Gonzales.