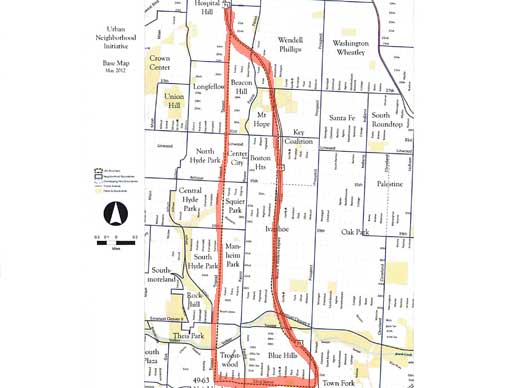

The target area for the Urban Neighborhood Initiative, one of the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce’s Big 5 Ideas. The plan is to boost the economy, develop cleaner and healthier neighborhoods, and increase educational opportunities in the area between Troost and 71 Highway, from 22nd to 52nd Streets.

After months of community meetings, city business leaders today presented a draft action plan for improving life in the Troost Avenue corridor.

The next step – implementing changes – will start in January in what advocates say is a unique public-private effort to change life between Troost and 71 Highway, 22nd Street to 52nd Street.

The action plan for the Urban Neighborhood Initiative (UNI) was presented today to about 250 community leaders, neighborhood advocates and business representatives at the Federal Reserve Bank in Kansas City.

It is one of five major initiatives identified last year by the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce. The action plan lists three strategies to improve life east of Troost:

- Prosperity, defined as increasing economic opportunity, reducing social disparities and establishing more mixed income housing.

- Health and Safety, which includes developing more safe and clean neighborhoods.

- Education, defined as improving its quality from birth through careers.

Brent Stewart, president and CEO of United Way of Greater Kansas City and co-chair of the UNI board, said of the effort: “It’s an opportunity to start changing the narrative of this area, to break down what historically has been a dividing line between black and white.”

Business and community leaders will work with citizens within the area to make long term changes, he said. “We knew we were going to be working with people, not doing something to people.”

Poverty, crime and housing problems that include high rates of foreclosure have plagued an area that has been ignored for too long, officials said.

Brian Smedley, director of the Health Policy Institute at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies in Washington, D.C., praised the UNI effort in a recent speech and talked about the problems of racial and ethnic disparities.

Just in health care alone, he said, black and Hispanic people who live in poor areas get lifetimes of lower quality care than whites, resulting in millions of dollars in public health costs and millions more in lost worker productivity.

In New Orleans, for instance, people have a life expectancy of 55 years in the central city and 80 in the nearby wealthy suburbs.

“When it comes to health,” he said, “your zip code is much more important than your genetic code.”

Some cities are starting to try to improve matters by not allowing more fast food and liquor stores to locate in some areas, he said, and by giving tax incentives for grocery stores to locate in places that need them.

Housing is also critical, he said, and the foreclosures during the recession have especially wiped out wealth of blacks and Hispanics.

For every $1 a white person has in wealth now, Smedley said, a black person has a nickel and a Hispanic person has 6 cents.

Communities nationwide are crafting place-based ways to respond to such problems, he said. “I don’t have to tell you about the power of people coming together.”

More than 700 residents participated in community conversations to help develop the action plan for the Troost Corridor.

Trackbacks