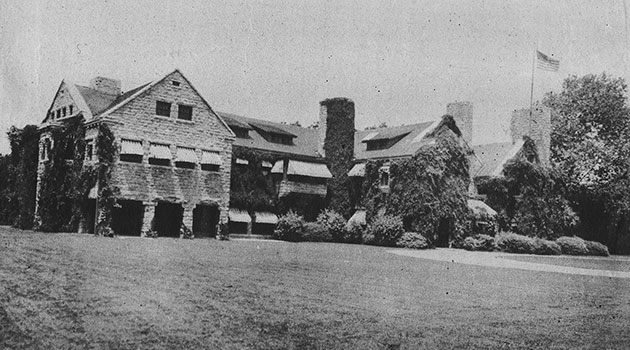

WIlliam Rockhill Nelson’s home, Oak Hall, 1890. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art now stands on the site.

William Rockhill Nelson is best remembered as the founder of the Kansas City Star, but Nelson once said he enjoyed nothing more than building houses.

Nelson the journalist was also an avid real estate developer and planner. He was among the first of the Kansas City elite to move south – helping start the movement of other well-off and middle-class people into the area that is now Midtown.

His home, Oak Hall, stood on 30 acres of land on the summit and slope of a hill overlooking Brush Creek. Rockhill bought the site in 1886. Most people of the time thought it would be a long time before the city reached that far south.

“When the site was selected, it lay two miles beyond the southern city limits, in a quarter that had been entirely neglected as a residence district, reached for the most part along unbroken roads, the most direct route to it leading through farmers’ fields and an old orchard,” according to the Kansas City Star’s book William Rockhill Nelson: The Story of a Man, a Newspaper, and a City, written in 1915.

For Nelson, the area became a laboratory for his love of designing neighborhoods and homes. He had previously built a development in today’s Union Hill that he used to show that small homes could be as attractive as larger ones. Around Oak Hall, he built Rockhill Road and planted trees along Warwick Boulevard. He built miles of rock walls and lined them with red roses. He also built small homes to be leased to his employees. The area developed into the Rockhill and Southmoreland neighborhoods after the turn of the century as Kansas City grew.

Nelson was a crusader for the City Beautiful Movement, a philosophy that beautifying cities through features like parks and boulevards would add to the quality of life and keep real estate values stable. City Beautiful ideals would play a huge role in the way Kansas City’s green spaces and thoroughfares developed. But in creating Oak Hall, Nelson was working on a smaller and more personal scale.

“Building houses,” Nelson said, “is the greatest fun in the world.

He planned every detail of Oak Hall. Nelson favored the native limestone quarried on his property as a building material, an unusual choice at the time because builders feared it would crumble. The result, however, was that limestone became a ubiquitous material for building as Kansas City continued to develop.

Nelson’s home stood apart architecturally from the mansions many wealthy Kansas Citians built at the same time. He allowed his ideas to evolve, gradually adding on over the years when he lived in Oak Hall.

“The great danger in building large homes,” Nelson used to say, “is that they look like a palace or a public institution. I have tried to build mine like a home.”

Oak Hall stood until the last of the Nelson heirs died in 1927 and donated the land to be used as a site for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Great article, thanks! …..I had no idea his house was the first to use Limestone b/c local builders had refused, supposing it would crumble – so he’s the reason most of our homes in Midtown have stone foundations & porches. He is featured quite a bit in Dona Boley’s new book on KC’s Parks & Boulevards.